Ancien régime of Gabon carries on under the guise of a military junta led by an army general directly related to the ousted civilian President

I. PREAMBLE:

Once again, I am going to be moving against the grain of opinion-makers in the alternative media space. I do this because I have a very good understanding of the continent of Africa and its history. Therefore, I’m able to analyse information in a very nuanced way and without injecting unnecessary ideology and sentiments into it.

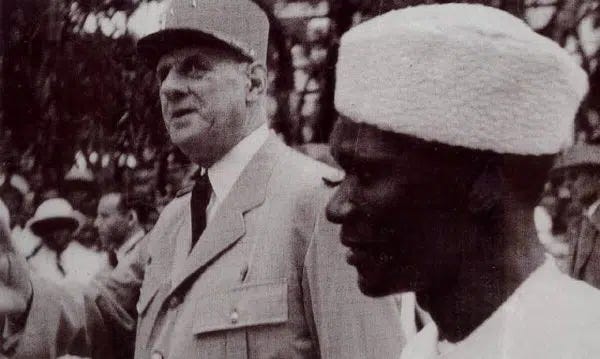

I have written previously about Gabon and profiled the man personally handpicked by General Charles De Gaulle to run the Francophone African state. I will highly encourage those who are interested to read this 2009 article, which I updated and reposted to Substack a few month ago.

II. GABON VERSUS GUINEA: THE HISTORY

In my fourth update on the Niger crisis, I digressed by going into the history of the one country that got away from the neocolonial yoke of France. That country was Guinea, which unilaterally declared its total independence from France on 2 October 1958 and promptly moved into the pro-Soviet orbit.

Well, Gabon was the opposite of plucky Guinea. Gabon wanted to move closer to France, which was then under pressure from the United Nations to grant independence to its colonies in Africa and Asia, especially after the British had come to terms with end of the era of great empires and had begun granting independence to its colonies starting with India (1947), Pakistan (1947), Burma (1948), Ghana (1957), Malaya (1957), Singapore (1958), Nigeria (1960), etc.

Initially, France wanted nothing to do with any talk of decolonization and sent its troops to go fight insurgents in Vietnam and Algeria in order to preserve its colonial empire. It created the supranational political entity, Union Française, to better integrate all its colonies ranging from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia in Asia to Gabon, Guinea, Senegal and Madagascar in Africa.

After France suffered a humiliating defeat in Vietnam and watched Union Française become moribund after the secession of Cambodia and Laos, the French colossus, General Charles De Gaulle, came up with a brilliant idea that would offer nominal “flag independence” to the remaining colonies in Africa while still keeping the Gallic state in charge.

The General offered a referendum which gave each colony three options:

Vote “no” in the referendum, become fully independent, and be cut off from all French support and developmental aid

vote “yes” and become an overseas province of metropolitan France

vote “yes” and join Communauté Française, a brand new supranational entity designed to transform the colonies into nominally independent client states of France.

Charles de Gaulle visited the colonies to personally campaign for a vote to join Communauté Française. In the colony of Guinea, the General famously forgot his trademark kepi cap on a conference table in the capital city of Conakry as he angrily stormed out of a meeting with the Guinean leader, Ahmed Sékou Touré, who said that Guineans would rather starve to death than agree to convert their homeland from a colony into a satellite state of France.

Guinea would end up being the only French colony in sub-Saharan Africa to vote in the referendum against membership of Communauté Française on 28 September 1958. And France would retaliate by destroying most of the infrastructure it had built on Guinean territory before pulling its colonial administrators, technocrats and military troops out. Thereafter, the abandoned colony declared itself a sovereign nation on 2 October 1958, making it the first francophone African nation to do so. It was also the first to drop the CFA Franc as currency after independence, and one of a few Francophone African countries without French troops on its territory.

Gabon was the exact opposite of Guinea. Charles de Gaulle was alarmed at the excessive Francophilia gripping Gabon. To his astonishment, local Gabonese politicians in the colony were instructing the populace to vote to become an oversees province of France. The General spent some time explaining to the local Gabonese politicians that it was in the best interest of the colony of Gabon to gain pseudo-independence and then join Communauté Française, which will allow France to maintain “supervision of everything.”

As Charles later told his confidant, Alain Peyrefitte, it was okay to take on the financial and managerial burdens of administering tiny Francophone Caribbean colonies that opted to become overseas departments (i.e. provinces) of France, but it was an anathema to allow a relatively large African colony like Gabon to become an integral part of France via the referendum.

“The Gabonese would remain attached to us like stones around our necks,” said the French leader. “I had a hard time trying to dissuade them [the Gabonese] from going for the option of an oversees province.”

In the end, a cajoled Gabon voted in the September 1958 referendum—along with other Francophone African colonies (except Guinea)— to join Communauté Française as a nominally independent nation.

Despite dropping the CFA Franc, having no French military bases and even severing diplomatic ties with France for a period of time, Guinea remains a basket case.

Ironically, Gabon, which stayed under French control, ended up having a much higher standard of living than Guinea and many other African countries, such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ethiopia, which were never under the yoke of French neocolonialism.

The data linked here does not lie or wear ideological clothes. Gabon is among the top ten in Africa with relatively decent Human Development Indices. It actually ranks seventh amongst the 54 nations of Africa while Guinea is ranked in the 45th place.

Now how is that for nuance?

So, we are faced with the cold fact that Guinea— whose national leader rightly defied France to win total independence— has ended up a total disaster because of the flux of political instability, engendered by the non-stop cycle of military coups. (Click here for details).

Most people think of coup d'états as removing the Head of State and that is it. No, coup d'états are revolutions that sweep away the Head of State along with existing institutions of that state. First act of all successful putschists is to revoke the constitution; suspend individual rights; abolish the parliament; abolish the judiciary or render it redundant; dissolve most or all governmental agencies established to deliver services. Basically, the coup leaders return the country to Year Zero.

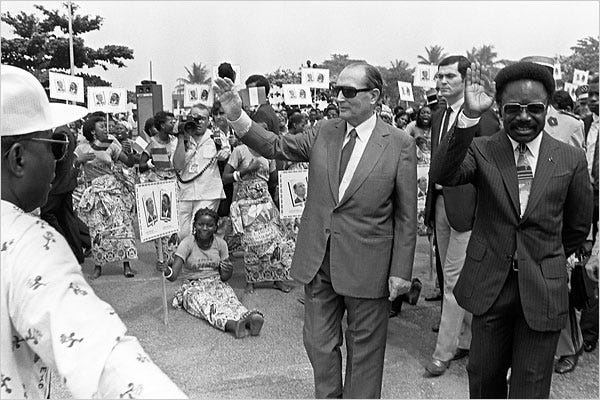

In contrast to Guinea, we have Gabon ruled by a corrupt man personally handpicked by Charles De Gaulle. That man, Omar Bongo, was never ashamed to justify the client status of his nation by repeatedly quipping:

“Africa without France is like a car without a driver. But France without Africa is like a car without petrol”.

And yet, unlike other natural resources-rich African countries under the same yoke of French neocolonialism, Gabon still managed to build a higher standard of living for its people amidst high levels of corruption.

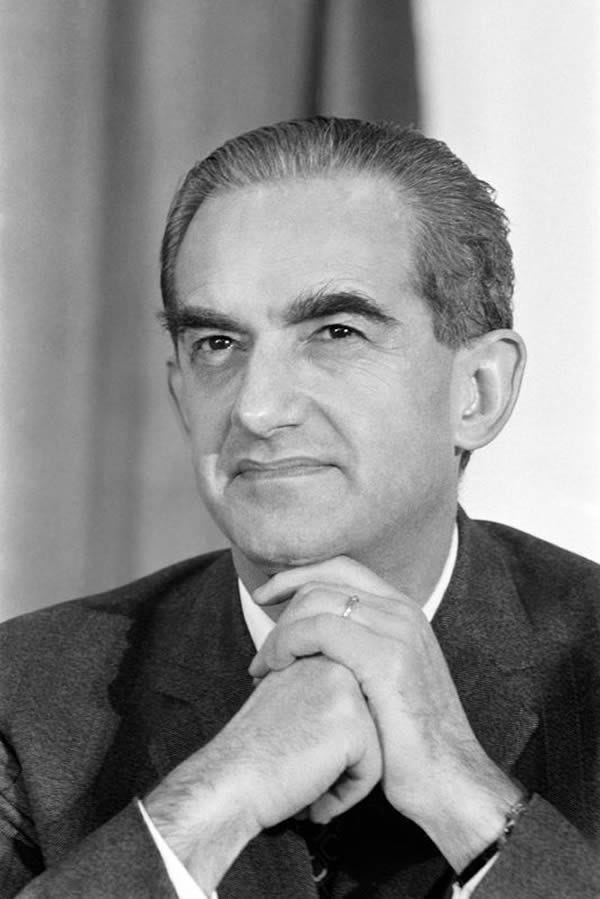

How did that happen? Well, over time, Omar Bongo managed to obtain a level of control and influence over his French handlers by using his nation’s oil wealth as leverage. He bankrolled French political parties both on the liberal and conservative wings of the political spectrum. He was one of the greatest friends of French leaders such as the Late Francois Mitterrand, Valery Giscard d’Estaing and Jacques Chirac.

Any French leader who offended the Gabonese ruler, even slightly, was punished by having the flow of cash diverted to his political rivals. For instance, former President Valery Giscard d’Estaing stated publicly in 2009 that Omar Bongo switched campaign contributions from him to his rival, Jacques Chirac in the run-up to the 1981 French Presidential Election. Mr. Chirac, who was facing a corruption scandal at the time, denied Valery’s allegation.

Chirac would eventually be tried for embezzlement, for creating fake civil service jobs for friends, and be given a two-year-suspended sentence in 2011.

Anyways, the skillful use of French businessmen as middlemen in the covert distribution of cash-stuffed briefcases to powerful French politicians bought Omar Bongo some level of independence to pursue the domestic policies that he wanted. Those policies included allowing a limited amount of the oil wealth to trickle down— just enough to prevent civil unrest.

Bongo achieved this through the building of schools, hospitals, universities and new towns, all of which were named after himself—Bongo University, Bongo Stadium, Bongoville town, several Bongo Hospitals, etc.

He employed as many ordinary Gabonese as possible in the bloated civil service to keep them on government payroll, to secure their loyalty, and minimize the risk of public anger or uprisings. Unlike many authoritarian rulers on the continent, he often preferred to buy off political opponents and only resorted to violence if all else failed.

The effect of Omar Bongo’s style of pacification was that Gabon remained politically stable for 42 years unlike other nations in the Central African subregion. That stability, despite all the corruption, allowed the injection foreign direct investment into the oil-rich country and the creation of jobs.

With 33% of its population being poor, Gabon still has a long way to go. But then Gabon is “paradise” compared to other Central African countries with 90% to 95% of their citizenry mired in poverty and civil conflict.

Gabon is also “paradise” compared to Bauxite-rich Guinea, which severed all links with France after it became a fully independent in 1958. Again, the difference between the two countries is— Political Stability.

Again, if you are interested in learning more about Gabon under the rule of the deceased President Omar Bongo, I would encourage you to read this:

Omar Bongo Ondimba: The death of a life president

**Important Note: This article was originally published in July 2009 ** On June 8, 2009, the one of the world’s longest serving rulers, President Omar Bongo Ondimba of the Republic of Gabon, died of intestinal cancer at a hospital in Barcelona, Spain. At the time of his death, he had ruled the central African nation of Gabon for 42 years and was accused …

Moving on…

III. ALI BONGO ONDIMBA AS LEADER OF GABON

States built by strongmen rarely survive the rule of their weaker progenies. Oliver Cromwell’s republican state, Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, barely survived the rule of his incompetent and weak son, Richard Cromwell. Within one year of Richard’s forced resignation, the republican state built by his father ceased to exist.

Gabon survived Omar Bongo’s death on 8 June 2009, but has been declining ever since under the rule of his son, Ali Bongo Ondimba, who had previously led a colourful life as a funk musician in the late 1970s and as the main organizer of Michael Jackson’s visit to Gabon in 1992.

In 1977, Ali Bongo, then aged 18, produced this funk song, A Brand New Man:

Ali Bongo became the presidential candidate of the ruling political party, Parti Démocratique Gabonais (PGD) after defeating his elder sister, Pascaline Bongo, in the internecine power struggle that erupted after the death of their father.

Pascaline had served in the government of her late father as Personal Adviser to the President of Gabon (1987-1991), Minister For Foreign Affairs (1991-1994) and Director of the Cabinet of the President (1994-2009).

In accordance with the constitution of Gabon, the interim government of Acting President Rose Francine Rogombe— which had succeeded the late Omar Bongo—organized a Presidential Election on 30 August 2009.

Ali Bongo narrowly won with 41.8% of the total votes cast and became President of Gabon while Rose Francine Rogombe reverted to her substantive role as President of the Gabonese Senate.

Dismayed supporters of the fragmented political opposition rioted in the streets, but that was quelled by law enforcement officers.

Once Ali Bongo had settled into the role of national President. it became clear to most observers that the man was nowhere as skilled as his father, and so power and authority began to haemorrhage from him.

Under the rule of Bongo Jr., healthcare services declined and the problems of constant electricity supply surfaced. Youth unemployment rate refused to budge from the 30% mark. These problems began to cause episodes of intense demonstrations, which Bongo crudely solved with riot police wielding batons and canisters of tear gas.

Since Ali Bongo was a man who spent his early adult life in show business, he decided that the best way to distract the angry masses from his failures was simply to bring famous celebrities to his country. To this end, he brought Pele to Gabon in 2012 and Lionel Messi in 2015.

In addition to inviting famous celebrities, President Ali Bongo briefly returned to his musical roots to entertain his disaffected citizens. Below is a video clip of him engaging with French-language hip-hop, a popular genre with some youths of Gabon:

Despite all the razzmatazz generated by famous celebrity visits and his own brief foray into music, sporadic outbreaks of mass protests by disaffected citizens remained a feature of life in Gabon.

In 2016, Ali Bongo “won” another controversial Presidential Election, sparking yet another round of violent protests.

In that Presidential Election, Bongo Jr. ran against Jean Ping who had been his father’s ally and a former lover of Pascaline Bongo. While still married to someone else, Jean had sired two kids with Ali Bongo’s sister.

Jean Ping, who is of partial Chinese ancestry, worked most of his adult life as a diplomat for Gabon in various agencies of the United Nations before serving in the government of the late Omar Bongo as a cabinet minister. From 2008 to 2012, he was Chairman of the African Union Commission.

During the NATO-sponsored civil war in Libya, Jean Ping tried repeatedly to organise peace talks between Gaddafi’s government and the jihadist rebels. When Sarkozy, Obama and Cameron blocked his efforts, he denounced them as “neocolonialists destroying Libya and destabilizing the region under the cover of the UN flag.”

In October 2018, Ali Bongo disappeared from public view. He had suffered a stroke, which forced him to seek treatment in Saudi Arabia and later on, Morocco.

When he eventually resurfaced in public on 1 January 2019, he was in a wheelchair. His weakness and paralysis was all there for all to see. Shortly after his reappearance, things quickly took a dangerous turn.

For the first time in 55 years, the relatively political stable Gabon witnessed a military coup d'état on 7 January 2019. The coup failed and the government of the partially paralysed President quickly reasserted control over the country. But it was obvious that more coup attempts would be made in the future.

IV. THE COUP D’ETAT OF 30 AUGUST 2023

As I have explained earlier, Gabon has been relatively stable country with a much higher standard of living compared to neighbouring central African countries, most of which were having coups after coups after coups interspersed with civil wars (e.g. Burundi and Central African Republic).

Well, the January 2019 coup d'état was the first sign that the Bongo ruling dynasty may be losing control of the state that its progenitor, Omar Bongo, had built with French support.

To digress a bit, I will like to point out to my readers that not every coup in an African country is ideological. In fact, for most of Africa’s history, coups were largely motivated by the personal ambitions of military officers pretending to be “saviours of the people”.

Given that context, it is wrong to automatically assume that every coup that occurs in a Francophone African country is “anti-French”.

Mali and Burkina Faso in West Africa are radically different from Gabon in Central Africa.

In a previous article, with relevant sub-section linked here, I gave a detailed explanation of why anti-French sentiments are visceral in Burkina Faso. It goes all the way back to the period following the October 1987 assassination of the extremely popular Burkinabe leader Thomas Sankara.

When I talk of non-ideological coups, I am referring to the March 2003 overthrow of pro-French civilian President Ange-Félix Patassé by pro-French Army General François Bozizé in Central Africa Republic.

I am also talking of the September 2022 overthrow of the virulently anti-French military regime of Colonel Henri-Paul Damibia by the virulently anti-French military regime of Captain Ibrahim Traore in Burkina Faso. Even the elected civilian government of Roch Marc Christian Kabore had a rocky relationship with the French government before it’s overthrow by putschists led by Colonel Damibia.

The successful coup d'état in Gabon on 30 August 2023 was prompted by yet another controversial Presidential election, which Ali Bongo allegedly won. However, the coup is in no way aimed at France or its interests in Gabon— at least for now.

The putschists installed Brigadier-General Brice Nguema as the military ruler, which is simply another way of saying that the mutinous soldiers aren’t really serious about real change.

The one-star general they put in charge of Gabon was a close associate of the semi-invalid Ali Bongo and has been implicated in the corruption of the Bongo ruling dynasty.

What is even hilarious about this affair is that the new Gabonese military ruler, Brigadier-General Brice Nguema, has the same surname as the ruler of neighbouring Equatorial Guinea, President Teodoro Obiang Nguema. But that is not the only similarity.

The new Gabonese military ruler is actually the first cousin of Ali Bongo, which makes the August 2023 coup a family affair not unlike the August 1979 coup in Equatorial Guinea, which saw Major-General Teodoro Obiang Nguema overthrow and then execute his own uncle, President Francisco Macías Nguema.

Teodoro Obiang Nguema ran Equatorial Guinea as a military ruler from 1979 to 1982. Then, he retired from the armed forces, wrote a new constitution and organized general elections. He subsequently transformed into a civilian President and has been running his “democratic” country ever since.

Are we going to get the same thing from the new Gabonese military ruler who happens to share the same surname as his counterpart in neighbouring Equatorial Guinea? Time will tell.

In the meantime, stacks upon stacks of cash embezzled by the toppled President is being found all over the capital city of Libreville.

As much as 70 billion CFA Francs ($155 million) was found in and around the home of Maitre Park, a South Korean friend of Ali Bongo who has been living in Gabon for quite some time. Loads of cash was also recovered from home of Ian Ngoulou, a personal aide to Noureddin Valentin Bongo, the 31-year-old son of Ali Bongo.

All of these discoveries have been shown on state TV in Gabon, causing outrage in the citizenry. The new military ruler has moved to pacify the populace, promising that public officials who embezzled money would be prosecuted.

Watch this short video clip of the new military ruler speaking to the press:

I am guessing the new Gabonese ruler would exempt himself from prosecution for his own financial misdeeds while working as the personal bodyguard of the cousin he ousted from power.

V. AFRICAN UNION REACTION TO THE COUP

Although individual countries in the West African subregion have condemned the military coup that toppled Ali Bongo from power, the organization, ECOWAS, has no role to play in Gabon as it is located in Central Africa.

The African Union does have a role to play. The pan African organization condemned the military coup d'état in Gabon and suspended its participation from the organisation just as it has already done to military-ruled Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger Republic.

Many readers who are unfamiliar with the post-colonial history of the Africa may not understand why the African Union is reflexively opposed to coups, some of which are supposedly seen as “anti-imperialist”.

The recent spate of coups occurring on the continent is actually a return to the past. If you had visited the continent in the year 1990, you would have noticed that nearly every African country was under the yoke of a military ruler and a significant number of them were in the middle of a civil war.

In the mid-1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, military coups were very common on the continent and in some cases, it set off a chain of events that resulted in devastating wars.

The January 1966 military coup in Nigeria was performed by young idealistic officers who wanted to end corruption in Nigeria. Unfortunately, that coup d'état set off a chain of events that resulted in the Nigeria-Biafra Civil War (1967-1970) that killed almost three million people.

The Liberian coup d'état of April 1980 set the stage for two civil wars (1989-1997 and 1999-2003). The January 1971 military coup in Uganda led directly to racially-driven expulsions of 1972 and the Uganda-Tanzania War (1978-1979). That coup also set the stage for the Ugandan Bush War (1980-1986).

Jihadist insurgency first became a serious regional issue in the late 1990s as a fallout of the Algerian Civil War (1992-2002), which was trigged by a military coup d'état that took place on 11 January 1992 to prevent the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) from taking political power in the North African state. The highly popular FIS had won the December 1991 parliamentary elections and was set to form the national government when the putschists struck.

Jihadist insurgents kicked out of Algeria simply decamped to the northern part of Mali and operated there.

NATO’s destruction of Libya’s statehood in October 2011 merely worsened the pre-existing problem of jihadi terrorism in the Sahel Belt. The origins can be laid at the door of the bloody civil war that lasted a decade in Algeria.

The Imperial government of Ethiopia was overthrown in a military coup d'état masterminded by Marxist soldiers on 12 September 1974. That coup led to the dissolution of the 704-year-old Ethiopian Empire and the installation of a Marxist-Leninist state in its place.

Within days of the coup, a group of disaffected Marxists opposed to the new communist regime took up arms, triggering the Ethiopian Civil War (1974-1991). The civil war between Marxist rebels and soldiers of the Marxist-Leninist state took 1.4 million lives—the bulk of those deaths being due to the famine that took place in the middle of the war.

General Mohammed Said Barre’s military coup d'état of October 1969 was welcomed by many in Somalia. However, the coup leader’s promotion of the Greater Somalia project— which sought to annex ethnic Somali areas of eastern Ethiopia and northeastern Kenya— eventually led to the disastrous Ethiopia-Somalia War (1977-1978).

The defeat of Somalia in that war led to internal political turmoil that eventually degenerated into the Somali Civil War (1981-present) and the country’s northwestern region unilaterally declaring itself the independent Republic of Somaliland on 18 May 1991.

Tolerance of coups was one of several reasons why the ineffective Organization of African Unity (OAU) was dissolved on 9 July 2002. Its replacement, the pro-integrationist African Union (AU), has since ruled that it would never recognize military juntas as they had been one of the causes of destabilization on the continent (apart from external meddling from USA and France).

VI. FRENCH REACTION TO THE COUP

Both mainstream and alternative media outlets have been gloating about the end of French influence in Gabon. They keep erroneously comparing Mali and Burkina Faso to Gabon despite the glaring differences in their histories and political cultures.

Here is a video of ordinary citizens celebrating the Gabonese military coup:

What do you notice about the civilian celebrants embracing soldiers who participated in the military coup ?

Well, there are neither Russian flags nor are there public denunciations of “French neocolonialism”.

Below, we have another one. This time, it is the video footage of soldiers in camouflage uniforms and some civilians celebrating the successful military coup. They are screaming, “we don't care about Ali Ben, he's cursed.”

Again, nobody is waving Russian flags or denouncing France. All vitriol is reserved for Ali Ben Bongo.

That may fly over the heads of people posting on YouTube, Telegram and Twitter. But it is important to understand that Gabon is nothing like Burkina Faso or Mali.

For historical reasons, the vast majority of Gabonese population are quite Francophile. In that respect, Gabon is a peculiar outlier in Francophone Africa.

Of course, the Macron government in Paris has issued a boiler-plate statement denouncing the military coup against Ali Bongo.

French government spokesman Olivier Veran said:

“France condemns the military coup that is under way in Gabon and is closely monitoring developments in the country, and France reaffirms its wish that the outcome of the election, once known, be respected.”

But the truth of the matter is that France is not worried at all about this military coup as the quietly pro-French Brigadier-General Brice Nguema is the new military ruler of Gabon.

Given Nguema’s direct family connections to the Bongo ruling dynasty, the French government does not feel that its close economic, diplomatic and military ties with the Central African country is in danger.

Nobody has called for the expulsion of the 400 French soldiers stationed in Gabon, even though France has suspended military cooperation with the new junta pending “clarification of the political situation.”

My dear readers, there is a good reason why French President Emmanuel Macron has not blown a gasket over the Gabon coup as he had done when putschists seized power in Niger Republic.

THE END

Dear reader, if you like my work and feel like making a small donation, then kindly make for my Digital Tip Jar at Buy Me A Coffee

Thank you Chima again for another comprehensive report and historical examination.

Would you expound a little regarding the controversial Ali Bongo election with in the context of Not being anti France or French interest... but then you state " at least for now". For what are you implying by saying, at least for now?

Excellent analysis once again. Thanks for this.