**Important Note: This article was first published in a student magazine in July 2009 **

On June 8, 2009, the one of the world’s longest serving rulers, President Omar Bongo Ondimba of the Republic of Gabon, died of intestinal cancer at a hospital in Barcelona, Spain. At the time of his death, he had ruled the central African nation of Gabon for 42 years and was accused of stealing billions of dollars belonging to his oil-rich nation.

From media reports, Bongo owned 33 properties in Paris and Nice with a combined value exceeding £125 million. A 1999 investigation by the US Senate unearthed $130 million in Bongo’s bank accounts in Citibank; money which the senators said were stolen from the Gabonese national coffers.

In spite of his corruption, Bongo was able to steer his nation for four decades without the kind of political unrest that plagued some neighbouring African nations and was actually quite popular among ordinary Gabonese people; the very people whose commonwealth he had embezzled.

The late President was born Albert-Bernard Bongo in 1935. After losing his father at the age of seven, he was sent to live with relatives in Brazzaville City in what is now the Republic of Congo [not to be confused with the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo]. After his primary and secondary education there, he embraced one of the few career options open to Africans under the French colonial regime— the French armed forces and colonial civil service. He worked for the colonial postal service briefly before joining the French Air Force in 1958. He was an air force lieutenant when Gabon gained independence in 1960.

While still serving in the French Air Force, Bongo’s political career took off when the discerning eyes of Charles De Gaulle fell upon him. Bongo was soon moved to the foreign affairs ministry of the nominally independent Republic of Gabon, and later on, posted to work in the private office of Gabon’s first President, Léon M’ba. Shortly after that, Bongo was promoted to Air Force Captain and then honourably discharged from the French military.

A military coup in 1964 in which he and President M’ba were taken hostage set the stage for further bonding between the two men and career advancement for Bongo. After French paratroopers flown into the country quashed the coup, Bongo was given charge of national defence and, three years later, became Vice-president when President Léon M’ba was re-elected to office.

Eight months into his second tenure, Léon M’ba died of cancer and Bongo succeeded him as President. The following year, in March 1968, Gabon was declared a one-party state.

Unlike most African leaders, Bongo was a strong supporter of French neo-colonialism in its former colonies and throughout his reign, Gabon was effectively governed as a client-state of France. He justified this by famously declaring that:

“Africa without France is like a car without a driver. But France without Africa is like a car without petrol”.

Charles de Gaulle, who had played a role in Bongo’s rapid advancement to power, was all too pleased to set up a French army base in the country to thwart any future coups or uprisings, thereby keeping his favourite Francophile in power indefinitely. In return, Bongo did whatever the French government ordered him to do, including giving the French oil company, Elf-Aquitaine, privileged rights to exploit Gabon’s petroleum reserves.

But influence and control did not always go in one direction: while it was without a doubt true that Bongo obeyed instructions from Paris, he also had influence in France, using oil wealth as leverage. He bankrolled French political parties both on the liberal and conservative wings of the political spectrum. He was one of the greatest friends of French leaders such as the Late Francois Mitterrand, Valery Giscard d’Estaing and Jacques Chirac.

Investigations into murky relationships with Elf, French politicians and businessmen in the 1990s exposed what has been described in the Financial Times as “Europe’s biggest fraud scandal since the second world war”. Investigators in Paris implicated several top French politicians, including President Mitterrand, in the bribery and corruption scandal in which the then French government–owned Elf-Aquitaine used oil revenues from its Africa operations to bribe politicians in France as well as rulers in oil-rich ex-colonies such as Cameroon, Gabon and the Republic of Congo.

In the Gabon, which sometimes provided 75% of Elf ’s oil revenues in Africa, the scandal was unique because France not only provided the usual regiment of army paratroopers, it also used the central African nation as a base for espionage activities and cash-based “diplomacy” in the adjacent West African region.

Though extremely corrupt, Omar Bongo did not fit the Western media stereotype of the brutal and humourless African dictator who kills political opponents at the slightest provocation. Though he trusted no one except the French government and members of his own family, he tried his best to accommodate every potential challenger to his rule.

While careful to appoint his son, daughter and in-laws to key positions in the foreign and defence ministries, Bongo made sure that those Gabonese politicians from ethnic nationalities other than his own minority Bateke ethnicity also occupied positions in government. Rather than brutally suppress dissent, Bongo pursued what Nigerians will call the “politics of settlement”. He “settled” all political opponents by offering them government positions or simply keeping them on the payroll.

In order to prevent civil unrest, he was careful to allow just enough oil revenues to trickle down to the 1.4 million-strong Gabonese population through the building of schools, hospitals, universities and new towns. These public works financed by government inevitably ended up being named after him— Bongo University, Bongo Stadium, several Bongo Hospitals, etc.

His hometown, Lewai, was rebuilt and was promptly renamed Bongoville. These public works kept Bongo popular in the sense that even poor Gabonese people observing the strife and chaos in some other African nations were able to say “at least we are able to feed ourselves and there is no civil war here”.

In line with his “settlement” policy, he responded to a nascent university protest led by students by providing about $1.35 million for the purchase of the computers and books they were demanding, which he felt was much easier to implement than dispatching troops and tanks to keep order.

But the politics of settlement had not always prevented conflict. In 1990, after mass protests, Bongo reversed himself and declared that Gabon was open to multi-party democracy. Other political parties were allowed to spring up and flourish. But allegations of massive vote-rigging led to further street demonstrations against him and the Police had to be called out to deal with the protesters.

The demonstrations ended suddenly when opposition politicians, after a series of meetings with Bongo, declared that they believed in “convivial democracy” and were given government positions.

When one leading opposition politician, Pierre Maboundou of the Gabonese People’s Union, refused to take government post and continued to criticize Bongo, he was not arrested or harassed. Bongo merely declared that he has “forgiven” the firebrand opposition leader. However, in 2006, the media reported that Maboundou had ended his non-stop fierce criticisms of Mr. Bongo. Speaking to journalists later, Maboundou justified his action, saying that the President had pledged to give him $ 21.5 million for the development of his home constituency.

On the international scene, Bongo cultivated the image of a compassionate man and peacemaker. During the Nigeria-Biafra war of 1967 to 1970, Gabon was one of five other nations that gave explicit recognition to the secessionist Republic of Biafra whose civil population was being starved to death and subjected to merciless aerial bombardment by the British-backed military junta ruling Nigeria at the time. Starving Biafran children dying of malnutrition due to the land and naval blockade of the Nigerian Armed Forces were taken to safety in Gabon.

When the International Red Cross stopped flying food into Biafra because the Nigerian military forces were shooting down their planes, Gabon became Biafra’s main means of flying in food to the beleaguered population until the war ended in Nigeria’s favour on 15 January 1970.

Bongo also played a central role in attempts to solve crises in the Central African Republic, The Republic of Congo, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

With the coming of Nicolas Sarkozy to power in France, many international pundits expected the relationship between Gabon and the French government to change. But such expectations were dashed when President Sarkozy demoted Jean-Marie Bockel the French minister in charge of dealing with ex-colonies in 2008. Sarkozy had taken action because Mr. Bockel had angered Bongo when he publicly criticized the “squandering of public funds by some African regimes”.

But then Sarkozy was less protective of France’s client African rulers than previous French leaders such as Jacques Chirac and Francois Mitterrand had been. Sarkozy refused to intervene when two French NGOs instituted legal action in 2007 against Bongo and two other rulers, Denis Sassou-Nguesso of The Republic of Congo and Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea for “misuse of public funds”. A furious Omar Bongo would later show his anger by going to Spain rather than France for medical treatment.

On March 14, 2009, Bongo was devastated when he lost his second wife, Edith, to an undisclosed ailment in Morocco. Edith was not only a trained pediatrician known for her commitment to fighting AIDS, she was also the daughter of the Denis Sassou-Nguesso of The Republic of Congo.

Months later, Bongo left for Spain on what the Gabonese government claimed was “a few days of rest to recover from the intense emotional shock of his wife’s death”. International media reports that he was seriously ill from cancer in a Barcelona hospital were strongly denied by the Spanish and Gabonese governments.

Later French media reports that Bongo was dead were also initially denied. But soon enough, these reports were confirmed by Gabonese Prime Minister Jean Eyeghe Ndong. Bongo had died of a heart attack shortly before 12:30 GMT on June 8, 2009.

The mourning of the corrupt ruler by ordinary Gabonese people probably shocked Western journalists who had expected the people to do the opposite. Of course, these journalists did not take into account the fact that Bongo was seen as a relatively benign, witty, charismatic and straightforward ruler who was “sensitive” to the people while engaging in widespread looting of the national treasury.

One of his legacies of “settlement politics” is a bloated and inefficient civil service whose main purpose was to keep as many ordinary Gabonese citizens as possible in government pay to secure their loyalty and minimize the risk of public anger or uprisings.

Another important legacy that most Gabonese appreciate is the peace and stability of his dictatorship. Not to mention the fact that under his rule, Gabon ranked 4th highest in Human Development Index in all of the sub-Saharan African region after Mauritius, Seychelles and South Africa.

The relative political stability of Omar Bongo’s regime had attracted a lot of foreign direct investment (FDI) over the decades. The combination of foreign investment, petroleum resources and a small population made Gabon the country with the 5th largest GDP per capita (PPP) in the entire continent of Africa after Seychelles, Mauritius, Equatorial Guinea and Botswana.

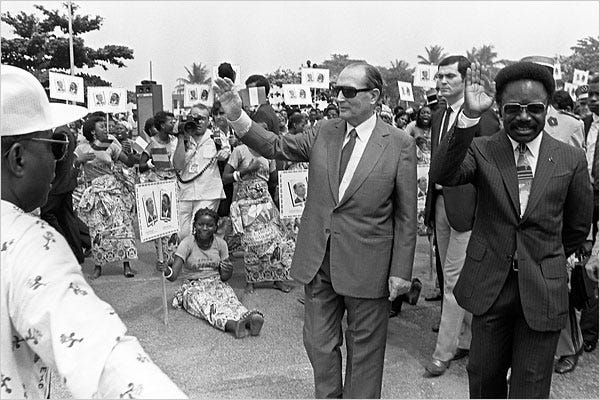

During the state funeral on 16 June 2009, ordinary people lined the streets in Gabon’s capital city of Libreville to bid farewell to the deceased ruler. It was attended by nearly two dozen African heads of state and only two western leaders, Nicolas Sarkozy and Jacques Chirac. According to Daily Telegraph reports, Chirac, who was a close friend of Bongo, was hailed by crowds at the state funeral while Sarkozy, whom Bongo had treated with contempt, was booed.

In the interim, Gabon is now governed by Mrs. Rose Francine Rogombe, the erstwhile Senate President, who is now expected to organize elections within 45 days. Pundits are expecting Ali Bongo, the defence minister and son of the deceased ruler, to become the next leader of Gabon. This has sparked calls by the political opposition for Ali-Bongo to be barred from contesting for office. So far the interim government has ignored the call and called for national unity. At the moment, the country is stable and it is generally agreed among African pundits that this would not change. Only time will tell for sure how Gabon will fare in the future without its colossus of a President who dominated the political scene for over four decades.

**UPDATE: In the 14 years that has passed since this article was originally published, the population of Gabon has grown to the current 2.4 million. The late Omar Bongo's son, Ali Bongo Ondimba, has since taken over as President of Gabon after controversial Presidential elections. The anti-French sentiments now sweeping Francophone African countries have largely not affected Gabon. In fact the small central African nation continues to enjoy good relations with France and is still hosting a huge French military base. Historically, Gabon has always been the most francophile of the ex-colonies of France. **

THE END

Dear reader, if you like my work and feel like making a small donation, then kindly make for my Digital Tip Jar at Buy Me A Coffee

Cons:

- loots the public treasury to the tune of several billion dollars

- nepotistic

- imperfect (but actual) succession plan

Pros:

- shares the loot across society

- makes sure even the poorest can eat

- buys off political opposition instead of shooting or imprisoning them

- listens when his people protest

- razor-sharp intelligent foreign policy

...where do I sign up?