ECOWAS : A PRIMER

ECOWAS in the larger context of Africa's historic interactions with China, France, USA, UK and Russia

PART I : 3D View versus 1D View

When it comes to the subject of Africa, many who comment on it have no idea what they are talking about. There is a generalized one-dimensional understanding that it is a place of poverty and wars, a geopolitical playground for “rapacious” neocolonial exploitation.

Of course, the devil is always in the details, but those three-dimensional “details” largely elude a lot of outsiders because they lack a comprehensive knowledge of the differing histories and political cultures of various countries on the continent. Because of lack of detailed knowledge, many commentators are simply not equipped to understand the nuances inherent in the complex web of relationships and interests that exist among various African states.

Due to their tendency to perceive African countries as passive subjects in an ongoing geopolitical struggle for influence, these commentators interpret every action taken by African states as either aligned with the “good” Russia-China axis or the “bad” USA-led NATO axis.

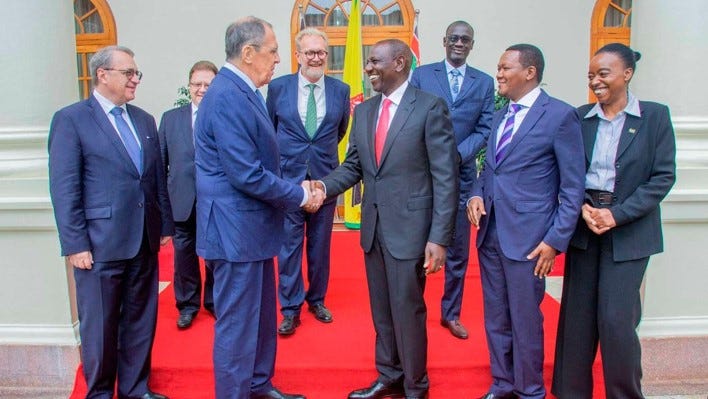

In the absence of knowledge, we get suppositions being passed off as analysis. We get “President Tinubu is US-French puppet” for wanting to enforce ECOWAS protocols. We get “Kenyan President Ruto is US puppet” because of his apathy towards Russia— a typical byproduct of being from an Anglophone African society, which is largely orientated towards the Western world.

The fact that the same Kenyan national leader argues for the abandonment of the dollar is ignored because having excellent diplomatic ties with the Collective West is a sure sign of “puppetry” :

Perhaps the truest indication of “puppetry” was when President Ruto rebuked Macron during an international finance summit in Paris for defending the World Bank and IMF.

“Nobody wants anything for free,” the Kenyan leader told Macron pointedly in response to the French leader’s promise that the EU would provide millions of dollars in donor packages to the continent.

“You are not listening,” the Kenyan leader told Macron before reiterating his demand for a new financial institution to be set up in parallel to the World Bank and IMF :

Maybe, Ruto’s personal boycott of the 2023 Russia-Africa Summit and his refusal to even send a single government representative to St Petersburg is the real sign of “American puppetry”—even as he seems to really admire the Chinese President Xi Jinping whom he constantly praises. Maybe the sign of the “puppetry” was on full display when he flew to Beijing to join in the celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative.

While in Beijing, he granted an interview to China Global Television Network (CTGN) during which he dismissed Euro-American media myths about “China trapping Africa in debt”. One doesn’t even need to listen to President Ruto. Two years ago, I wrote a whole article about China writing off the debts of African countries.

Anyway, here is a short clip of Ruto with his CTGN interviewer:

Talking of the 2023 Russia-Africa Summit, one can somewhat discern the differing geopolitical perspectives of Francophone and Anglophone Africa by taking a closer look at the 19 African national leaders that personally went to St Petersburg.

Ten out of the nineteen Heads of State and Heads of Government who attended summit were from French-speaking African countries. In other words, 53% of the national leaders who bothered to turn up at St Petersburg were from increasingly russophile Francophone Africa. By contrast, only 16% of the national leaders— three Heads of State— who came to the summit in person were from Anglophone Africa.

Five Anglophone countries, namely Kenya, Botswana, Mauritius, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, boycotted the summit completely by declining to send any official representatives to St. Petersburg.

President Ruto also told the local media in Kenya that it was “inappropriate for Russia to be hosting a summit in the middle of a war.” He also criticized other African leaders for going to Russia.

Again, this apathy towards Russia is simply a reflection of the general sentiments of the wider Kenyan society, which leans heavily in the pro-Western direction.

Kenyan apathy should not be construed as a sign of hostility towards Russia. The East African country continues to enjoy amicable relations with the Eurasian giant. In fact, William Ruto and his predecessor, Uhuru Kenyatta, remain grateful to Russia for defending them against the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2010.

Countries friendly to the USA, such as Kenya, Ghana, Botswana and Liberia, may not necessarily be keen on deepening their relations with Russia, but China is a completely different matter. None would pay any attention to requests by USA or Western Europe to downgrade ties with Beijing.

Ghana has good ties with Russia, much better ties with China, but its priority will always be to maintain excellent relations with the Collective West— as is the case in all Anglophone African states (except South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe).

While Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo may desire strong relations with the USA and UK, it does not mean he is subservient to either of them. This fact became evident during the visit of US Vice President Kamala Harris last year.

In March 2023, two “dignitaries” from the Western world visited the continent. French President Macron visited four African countries at the beginning of that month. In French-speaking Democratic Republic of Congo, an ex-Belgian colony, public demonstrations broke out as soon as Macron’s plane landed in the capital city of Kinshasa. Congolese protesters waved Russian flags and shouted anti-French invectives.

Later on, an affronted Macron delivered a blistering speech to an audience of Congolese university students, arguing that “France is not responsible for Africa’s problems with sovereignty”.

During an embarrassing joint press conference, the French leader engaged in a public spat with the Congolese President, who accused France, Western Europe and USA of disrespecting his country, and made snide remarks about the controversial 2020 US Presidential Election.

Towards the end of that same month, US Vice-President Kamala Harris visited Ghana, Zambia and Tanzania. There were no angry street demonstrations in any of those Anglophone African countries. Kamala was well received by cheering crowds in all three English-speaking African countries as shown my video montage below:

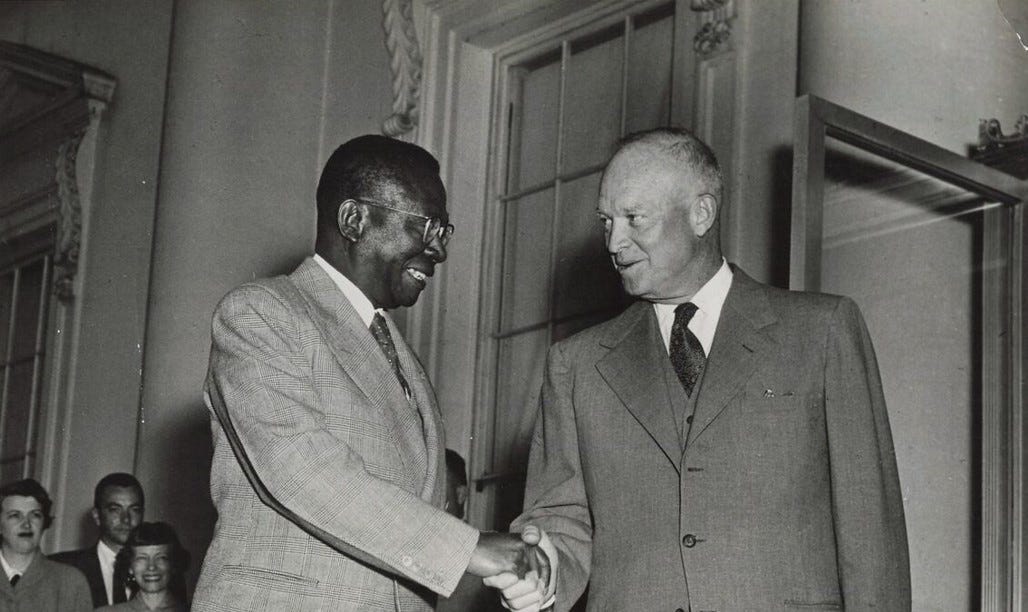

During her visit to the Ghanaian city of Accra, President Nana Akufo-Addo gave a long speech in which he recounted how many Ghanaians had benefitted from US government grants to study in American universities during the 1950s and 1960s. He also spoke affectionately of links between the Ghanaian nationalist leaders and Black American civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King and W.E.B Dubois who spent his final years in Accra and died there on 27 August 1963.

And yet after paying tribute to his country’s strong relations with the United States, the same President Nana Akufo-Addo brusquely refused Kamala’s request that Ghana downgrade ties with China. He also rejected her attempt to intervene in a legislative bill concerning sexual morality going through the Ghanaian Parliament, stating that it was not the business of USA to interfere with it.

During the joint press conference with Kamala Harris, the Ghanaian national leader defended his country’s good relations with China to an enquiring American journalist. Watch subtitled video below:

In both Tanzania and Zambia, the US Vice-President was warmly received, especially in the latter where her Indian grandfather had worked as a senior government official in the 1960s. In spite of the warm reception, neither Anglophone country agreed to Kamala’s request to distance themselves from China’s embrace.

Hilariously, Kamala had entered Zambia through an international airport built by a Chinese company, and yet she did not see the irony of asking the copper-rich country to downgrade ties with Beijing. Perhaps, she was unaware of the history of the airport, which is not the only aerodrome built or refurbished by China in recent years.

In Tanzania, Kamala gushed over the fact that Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan is female. The Tanzanian national leader heard Kamala’s proposal of $500 million in financing to help U.S. companies export goods and services in various sectors of the economy. She expressed her gratitude to the American visitor, but ties with China remained solid.

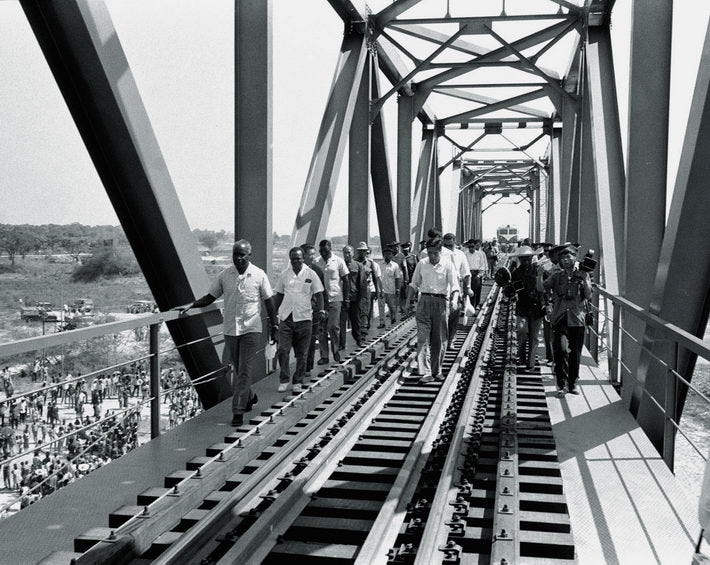

Tanzania and Zambia, while maintaining friendly relations with USA, UK and continental Europe, have a lasting memory of how China, a poor country in the early 1970s, put some of its own domestic infrastructural needs on hold, in order to construct the iconic Tanzania-Zambia Railway (TAZARA).

The rail project was conceived in the 1960s as a proactive measure against any potential attempts by apartheid South Africa to stymie the economic development of landlocked Zambia by denying access to its sea ports.

In 1965, Mao Zedong made an unsolicited offer to build the 1,860-kilometer-long railway connecting copper-rich Zambia to the sea ports of Tanzania. The offer was not taken up.

Julius Nyerere, then the President of Tanzania, was reluctant to agree to such an offer as poverty-stricken China was itself in dire need of infrastructure. Mao said China would postpone some domestic rail projects to help Zambia and Tanzania, but Nyerere still refused to take up the offer.

Nevertheless, at Mao’s insistence, he allowed a team of Chinese surveyors to visit the Tanzanian site selected for the rail project. In October 1966, the Chinese team completed a brief report outlining their findings.

At the moment in history, both Zambia and Tanzania were governed by popular national leaders who had embraced the highly heterodox “AfroSocialism”— a blend of Fabian Socialism, traditional African communalism, a degree of collectivization, self-reliance verging on complete autarky, and a total rejection of class struggle, revolution, and atheism.

AfroSocialism was treated with contempt by many doctrinaire Marxist-Leninists, both within and outside of Africa, who considered its tenets to be “reactionary”.

Julius Nyerere of Tanzania was a devout Roman Catholic and sought good relations with UK, USA, USSR and China. His Afro-socialist counterpart in Zambia, President Kenneth Kaunda, also maintained good relations with China, the NATO countries and Warsaw Treaty nations, but his diplomatic emphasis remained with the United Kingdom and fellow Commonwealth countries in Africa and Asia.

It was those Commonwealth ties that made it easy for Kaunda to get India to loan some of its technocrats to Zambia. A good example of such a technocrat was Painganadu Venkataraman Gopalan who also happened to be Kamala’s maternal grandfather.

Unlike Nyerere, President Kaunda was wary of any “communist involvement” in the rail project. He turned down an offer from the Chinese Ambassador to build the railway, and approached rich West European states for help.

Meanwhile, Nyerere, who was reluctant to overburden poverty-stricken China, approached the wealthier Soviets for help.

Both African national leaders got nowhere. UK, Japan, West Germany, USA, Soviet Union, World Bank, and United Nations, all declined to provide any funds for the rail project.

Finally, Kaunda dropped his objections and accepted Mao’s offer while visiting China in January 1967.

As one would expect, US government and its media allies promptly began a propaganda campaign. They claimed that China would build a “poor quality bamboo railway”.

Wall Street Journal said the following in 1967:

The prospects of hundreds and perhaps thousands of Red Guards descending upon an already troubled Africa is a chilling one for the West.

The British Prime Minister Harold Wilson smiled smugly when he heard that Zhongnanhai would fund and build the long railway. “China has got no money to do it,” he assured any NATO country leader that raised the issue.

But the Americans did not wait to find out if Wilson was correct. They rushed to fund their afterthought project, the Tanzania-Zambia (Tanzam) Highway, to compete with China’s then incipient TAZARA project.

The American-funded highway was built in phases, from 1968 to 1973. On the other hand, the Chinese government built TAZARA from 1970 to 1976.

By early 1970, both rival projects had begun to literally proceed side by side, and later intersected at a bridge spanning the Great Ruaha River in southern Tanzania. That bridge was the site of a clash between American road builders and Chinese railway workers on 3 March 1970.

Upon completion in 1975, TAZARA proved to be a lifeline for the economy of copper-rich Zambia. The railway enabled the landlocked country to avoid total dependence on sea ports controlled by an apartheid South African government upset at Zambia’s clandestine support for ANC irregulars within South African territory and SWAPO guerrillas fighting South African troops illegally occupying their country, Namibia.

By avoiding South Africa’s sea ports, Zambian copper was also evading transit through the territory of the unrecognized Rhodesian State (1965-1979), which was then conducting military raids deep inside Zambia to target the rear bases of Marxist-Leninist ZIPRA and Maoist ZANLA, the rival guerrilla forces engaged in a war to overthrow the local white ruling elites of Rhodesia and establish a new state called Zimbabwe.

Prior to the existence of TAZARA, the copper travelled exclusively along a British-built colonial era railway that linked the landlocked countries of Zambia and Rhodesia to the sea ports of apartheid South Africa. However, due to strained relations between Zambia and those two states, both international pariahs for their racially discriminatory policies, it was not prudent to depend on them for sea access.

Zambia could not use the alternative sea ports of either Mozambique or Angola as both Marxist-run Lusophone countries were embroiled in civil wars with nihilist death squads armed to the teeth by apartheid South Africa and USA.

TAZARA remained the only means of moving huge volumes of Zambian commodities to sea ports without passing through apartheid South African-held territories from 1975 until Namibia gained its independence in 1990 following the end of the South African Border Wars (1966-1990) and the emergence of post-apartheid South Africa in 1994.

Today, TAZARA no longer has the privilege it once enjoyed. Zambian copper can now be transported through various alternative railways leading to sea ports in South Africa and Namibia. The end of civil wars in Mozambique (1992) and Angola (2002) opened up more sea ports connected to railway lines for Zambian copper.

TAZARA project was China’s first major construction project on the African continent. Between 1965 and 1976, China sent thousands of people to Tanzania and Zambia. As already stated, the first group from China were surveyors who came to do feasibility studies from 1965 to 1966. The second group were the 30,000 to 40,000 Chinese workers, either drawn from the railway engineering corps of the People’s Liberation Army or from personnel of the (now defunct) Ministry of Railways.

About 60,000 railway workers from Zambia and Tanzania worked alongside their Chinese counterparts during the construction of TAZARA. More than 160 workers, including 64 Chinese citizens, died in accidents during the building of the 1,860-kilometer-long railway line.

According to the website of the Chinese Embassy in Tanzania, the railway was the largest single foreign-aid project undertaken by the East Asian country anywhere in the world as of the year 2012. The construction cost to the then poor China was a whopping 500 million dollars— the equivalent of US $2.94 billion today when adjusted for inflation.

China did not complete the construction of another wholly new railway line on the continent for another four decades until the opening of Nigeria’s Abuja–Kaduna Railway in 2016; the 2017 commencement of Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway services in Kenya, and the formal start of commercial operations on the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway in Ethiopia and Djibouti on 1 January 2018.

Click on any picture below to activate photo gallery:

Was Kamala Harris told this fascinating story by State Department officials before going to either Tanzania or Zambia to request a downgrade of ties with China? I strongly doubt that she was briefed.

Anyway, the point I am making in this section of the article is that certain African countries, cautious of history, often try to balance between the big geopolitical powers. Sometimes, they prioritize relations with one geopolitical power over the other.

African leaders engaging in such behaviour aren’t anybody’s puppet as caricatured by certain clueless opinion makers in the alternative media universe.

Of course, many African leaders may be personally corrupt, but that does not negate anything I have written so far. For instance, Nigeria is an utterly corrupt country. Nevertheless, its venal ruling elites still retain a degree of national pride and see the vast multiethnic country as the “Giant of Africa”. The idea that Nigeria would simply surrender its own hegemonic regional interests to any external power (e.g. France or USA) flies in the face of history.

In the early 2000s, Nigeria rejected US President George Walker Bush’s repeated attempts to locate African Military Command (AFRICOM) headquarters anywhere in West Africa. When Liberia said it was willing to host the headquarters, Nigeria sent an immediate démarche to the Liberian government, which at the time was reliant on Nigeria’s Police and Army to keep law and order within its war-devastated territory.

For similar reasons, South Africa blocked any attempt to locate AFRICOM within the wider Southern African subregion. Egypt, Algeria and Libya also opposed the siting of the headquarters of the US military formation anywhere within North Africa. As a result of this, AFRICOM is still headquartered in its “temporary” location of Stuttgart, Germany, almost two decades after the African continent rejected it.

While in office, President George W. Bush, and, later on, President Barack Obama, repeatedly offered American troops to “help” Nigeria’s fight against jihadi terrorists. On each occasion, Nigerian national leaders politely declined the “help”—preferring to use its own armed forces for that purpose.

Eventually, those unsolicited American troops, initially offered to Nigeria, ended up in neighbouring Niger Republic with the ostensible task of “training Niger soldiers to fight terrorism”. Even as France is being forced to evacuate their 1,500 troops, the Niger military junta is quite happy to let 1,100 American troops stay.

Obviously, it goes without saying that disagreeing with the Americans on certain issues is not an indication that Nigerian national leaders are less pro-Western than ruling elites of other Anglophone states such as Ghana, Botswana or Kenya.

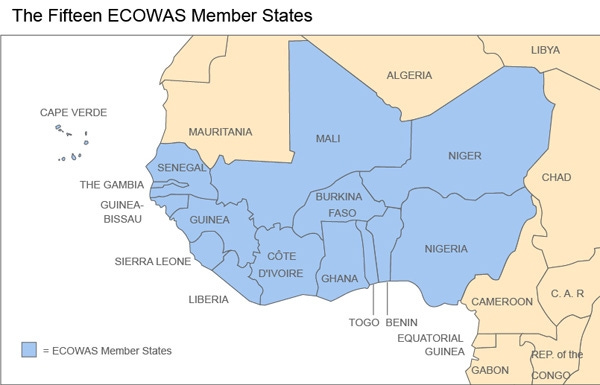

PART II: ECOWAS In Proper Context

1. AFRICAN STATES INTERVENING IN OTHER AFRICAN STATES

Outsiders unfamiliar with Africa’s intricate history often find it perplexing why Nigeria or any other African country would involve themselves in the affairs of a neighboring sovereign state. Many assume that African states have no national interests that extend beyond their immediate geographic boundaries and automatically interpret any intervention beyond their borders as serving the interests of external powers from North America or Western Europe. Of course, these assumptions are nonsense that does not accord with historical evidence.

Algeria’s intense diplomacy within the African continent is mostly responsible for the recognition of Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) as a sovereign country with the exiled Polisario Front as its provisional government.

Outside the continent of Africa, the SADR is mostly not recognized as a sovereign state. It is identified as “the disputed territory of Western Sahara”.

The Polisario Front is financed by Algeria and its leaders are largely based in the city of Algiers from where they administer 20% of the land contested with Morocco.

The Kingdom of Morocco considers the “disputed territory” to be one of its provinces, and Algeria to be an aggressive interloper for equipping the military wing of Polisario Front in its armed conflict with the Royal Moroccan Armed Forces.

As far as AU is concerned, there is no dispute at all. Morocco is simply occupying 80% of the territory of SADR, which became a full member of the now defunct Organisation of African Unity (OAU) on 22 February 1982 due to intense lobbying from Algeria.

Algeria was the first to recognize SADR as a sovereign state on 27 February 1976 and pressed other African nations to do the same thereafter.

The African Union (AU), which replaced OAU in 2002, continues to affirm SADR as one of its member-states. The rest of the world may think there are 54 countries in Africa, but the African Union, on its official website, says there are 55 countries. SADR is the reason for that discrepancy.

Algeria is not the only example of an African state that have intervened in matters outside its own borders. As already covered in a previous article, Tanzania provided refuge to Ugandan President Milton Obote after his overthrow in a military coup led by General Idi Amin on 25 January 1971.

From 1971 to 1978, the government of Tanzania provided political support and weapons to Ugandan exiles and allowed them to operate rear bases in Tanzanian territory from where they regularly launched cross-border raids into their native country. The Idi Amin-led military regime denounced Tanzania for interference in the internal affairs of Uganda and bombed Tanzanian border towns in retaliation for the cross-border raids.

On 9 October 1978, Tanzania People’s Defence Force (TPDF), accompanied by proxy Ugandan rebel forces, launched a full-scale invasion of neighbouring Uganda, triggering the Uganda-Tanzania War (1978-1979), which got rid of the Idi Amin regime and installed a provisional government in its place. By December 1980, the provisional government had vanished and the previously exiled President Milton Obote was back in charge of Uganda.

At the time of his overthrow, Ugandan military ruler Idi Amin was an enemy of UK and Israel. From an outsider’s perspective, one might be tempted to conclude that Tanzania was doing the bidding of the British and Israelis. However, such would be the conclusion of a person who is clueless of the situation in the East African subregion at the time.

In the years leading up to the war, there was a steady stream of Ugandan refugees fleeing Idi Amin’s erratic and cruel military junta. Many of those refugees ended up in neighbouring Tanzania, creating a humanitarian crisis. To make matters worse, Idi Amin had annexed the Tanzanian region of Kagera, claiming it rightfully belonged to Uganda.

Regardless of how you cut it, Tanzania acted in its national interest, not that of Israel or UK. Although Tanzania maintained amicable relations with Israel and UK, its heterodox socialist leader, Julius Nyerere always treasured his independence. He had actually spent a large part of his adult life in the anti-colonial struggle in British-ruled East Africa.

Of course, none of these facts stopped Idi Amin— who positioned his regime as “anti-imperialist”— from portraying Julius Nyerere as a British-Israeli puppet, thus persuading a youthful Colonel Muammar Gaddafi to send Libyan expeditionary troops to Uganda. Yasser Arafat even sent Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) fighters to Uganda to defend against the invading Tanzanian army.

Thirty years later, on 25 March 2008, the same Tanzania would participate in the military invasion of the rebellious island province of Anjouan to douse the political crisis afflicting one of the three island provinces that constitute the Union of The Comoros.

The decision to employ force in March 2008 to oust Colonel Mohamed Bacar, who had taken control of the island province of Anjouan following a coup d'état in 2001, was controversial.

Republic of South Africa—the powerhouse and hegemon of Southern Africa— was stridently opposed to any military action within the territory of the Island country of Comoros, which is considered to be part of the subregion. Nevertheless, Tanzanian, Sudanese, Senegalese and Comorian national troops invaded Anjouan Island with logistic support provided by Gadaffi’s Libya.

Despite its vociferous opposition to military intervention in Comoros, Republic of South Africa is by no means a pacificist country. The post-apartheid state has also intervened politically or militarily in the affairs of smaller countries in its own neck of the woods.

On 22 September 1998, South African-led SADC troops intervened militarily in neighbouring Kingdom of Lesotho to restore order after mass riots broke out and the armed forces of the small kingdom mutinied, which raised concerns about an imminent military coup.

In 2014, there was another coup d'état in the same Lesotho. South Africa threatened to send in its troops, but ultimately didn't because the coup leaders fled ahead of the planned military intervention, leaving the South African police to escort exiled officials of the overthrown royalist government back to their country to reclaim political power.

Obviously, South African government was not acting in the interest of any external geopolitical power. It is was simply acting to protect its national interest, which was not served by any form of political instability within the wider Southern African subregion.

There is nothing strange about this. Large African nations, such as Nigeria, Egypt and South Africa, with more advanced economies, generally tend to have huge national and regional interests that need protection.

Even a large country with a relatively small economy such as Ethiopia does what it can to protect its national interest, which is why it is attempting to formalize its long standing relationship with the unrecognized Republic of Somaliland despite the disapproval of other states in the Horn of Africa, including Somalia, which rejects the independence of the secessionist state.

SIDE BAR: SEA ACCESS IS A CORE NATIONAL INTEREST OF ETHIOPIA

Sea access is a core national interest of landlocked Ethiopia as espoused by its incumbent Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed.

Without a cheap, reliable way of reaching the Red Sea, Ethiopia’s socio-economic development will continue to encounter obstacles due to the elevated costs of engaging in seaborne trade that must necessarily transit through littoral states, some some of which may not necessarily have the best relations with the huge landlocked country.

Consequently, Ethiopia has pivoted towards building stronger relations with the secessionist Republic of Somaliland, defying the national government of dysfunctional Somalia, which does not recognize the independence of the breakaway state.

In the future, I intend to write an article on Ethiopia-Somaliland relations, which dates all the way back to the year 2000 when Meles Zenawi, then Prime Minister of Ethiopia, realized that his large landlocked country badly needed Somaliland’s Port of Berbera after Eritrea banned access to its two sea ports on the Red Sea at the end of the Eritrea-Ethiopia War (1998-2000).

Another motive for seeking access to Somaliland’s Port of Berbera is the ludicrously high service fees that Republic of Djibouti charges desperate Ethiopia to use its sea ports.

Everything you need to know about the back story of the unrecognized Republic of Somaliland can be found in this July 2008 article, which I cross-posted to Substack. For the benefit of readers, I have added some extra information to bring the old article up to date :

Just like South Africa, the Nigerian Federation is regional powerhouse that has an interest in preserving the security of the West African subregion. ECOWAS is one of the tools employed in the service of that objective.

I seize this opportunity to reiterate what I wrote in a previous article:

Nigeria has a history of military interventions in the West African subregion. If not for the current geopolitical climate, Nigeria's latest intervention would have largely passed unnoticed by many commentators outside the subregion just as happened when Nigeria intervened in Liberia (1990, 2003), Sierra Leone (1997), Guinea-Bissau (1998, 2012, 2022) and Gambia (2017).

Twenty days before Russian troops entered Ukraine, Nigeria organized the third ECOWAS military intervention in Portuguese-speaking Guinea-Bissau.

You may have missed that interesting piece of information because neither USA nor France showed more than a passing interest in what ECOWAS was doing on 4 February 2022. None of those two NATO countries had much to do with Nigerian-led troops entering Guinea-Bissau, which meant that the usual self-proclaimed “experts” in alternative media were unable to fabricate a narrative for their audiences, claiming that then Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari was merely a “puppet of France and USA”.

The third military intervention in Guinea-Bissau occurred a decade after the previous intervention in 2012. Interestingly, earlier that year, US President Barack Obama had lobbied hard for Nigeria to send troops to Somalia to fight Al-Shabaab terrorists.

Goodluck Jonathan— then the incumbent Nigerian President—had politely refused because Nigeria has no security interests in Somalia beyond making sure that its commercial ships were not hijacked by seafaring pirates. But that same year, Nigeria organized for ECOWAS troops to intervene in Guinea-Bissau where it has real regional security interests.

2. NIGERIAN CREATION OF ECOWAS:

Before I go any further, I will to state that there are three organizations that Nigeria diligently funds and controls in order to secure its regional and national security interests. They are as follows:

The first two organizations listed above had no initial regional security roles when they were founded, but over the decades, both expanded their remits.

ECOWAS evolved from a purely trade organization to one with a mission of greater regional integration in the political, educational, cultural and military spheres. Similarly, LCBC, which initially focused on regional water resource management, expanded its scope to include counterterrorism in order to address unforeseen security challenges that first arose in the Chad Basin Area during the Algerian Civil War (1992-2002).

Jihadi terrorism first became a serious regional issue in the late 1990s as a fallout of that civil war, which was triggered by the coup d'état carried out by the Algerian Army on 11 January 1992. In the course of the ensuing war, many jihadi insurgents kicked out of Algeria simply decamped to the Sahel. Within a few years, their terrorist activities in Southern Algeria and Northern Mali had spread to Niger and Chad.

The destruction of Libya’s statehood in late 2011 merely turbocharged the pre-existing problem of terrorism. The same air-dropped NATO weapons used by Libyan jihadists to topple Gaddafi’s government in October 2011 entered the hands of Islamic terrorists active in Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad and the northernmost fringes of Nigeria.

A while back, I wrote an article discussing a Lake Chad Basin Commission meeting summoned in November 2022 by then Nigerian President Buhari to discuss an intelligence report by three Nigerian security agencies (NIA, SSS, DIA) analyzing the prospect of NATO weapons in Ukraine finding their way into the Lake Chad Basin Area, which overlaps with the jihadi-prone Sahel Belt.

The meeting summoned by Nigeria was attended by national leaders (or representatives) of all eight countries that belong to LCBC, namely: Algeria, Libya, Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Central African Republic, Sudan and Nigeria.

In contrast to LCBC and ECOWAS, the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) was a purposeful security task force created by Nigeria in 1998. The origin story of the MNJTF dates back to 1994 when Nigerian military ruler Sani Abacha made the decision to create a task force composed solely of Nigerian troops to address cross-border security issues. Four years later, this exclusive Nigerian security task force expanded to include troops from neighbouring Niger, Benin, Cameroon and Chad, thereby giving birth to the multinational military force.

Over the years, Nigeria has unashamedly used all three organizations it either created or co-founded as tools for its national and regional security interests.

Altogether, these different organizations have given Nigeria a forum for discussing regional security with 15 West African states, 2 North African states and 4 Central African states.

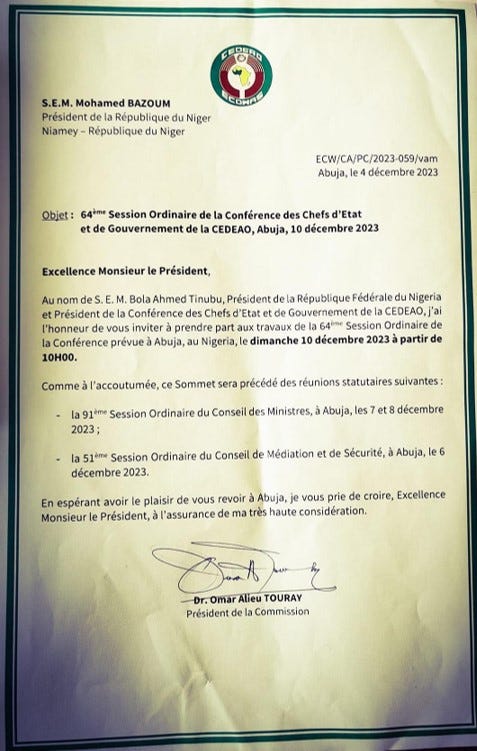

To understand why ECOWAS reacted the way it did to the Niger coup’ d'état of 26 July 2023, you need to understand what the organisation is all about.

As already stated, Nigeria is the regional hegemon of West Africa. One of the few in Africa that has a formidable army, air force and navy. Despite relying heavily on Russia, Turkey and China for military equipment, the Nigerian Army does make some of its own lightly armoured vehicles. Nigerian Airforce makes small reconnaissance drones. And the Nigerian Navy designs and makes some of its own patrol vessels.

SIDE BAR: EXAMPLES FROM THE CIVILIAN MANUFACTURING SECTOR

Nigeria also has a small civilian manufacturing sector. Although, there are Nigerian companies making various things like shoes, pharmaceuticals, electric power cables, plastics, industrial chemicals, motorcycle spare parts, vehicle batteries, I will only discuss a few examples.

Zinox Group is a private Nigerian company that assembles computers, tablets, laptops and household appliances since 2001.

I have already written this Substack article about IVM Limited, a vertically-integrated domestic vehicle manufacturer in Eastern Nigeria that makes its own buses, luxury saloon cars, SUVs, trucks and military vehicles. IVM Limited has several subsidiary companies that locally fabricate 70% of the components used in the making the vehicles. The remaining 30% are imported from abroad.

There is also Nigeria’s petrochemical sector, which includes both government-owned and private fertilizer companies. In fact, a new privately-owned fertilizer plant opened in Nigeria in March 2022.

The new fertilizer plant owned by Nigerian conglomerate, Dangote Group, is the largest granular urea plant anywhere in Africa and the second largest in the world. It is capable of producing three million metric tonnes of fertilizer annually. Its owner says that the plant is already receiving massive supply orders for fertilizer from the European Union.

Interesting video footage of that fertilizer plant can be found inside this old Substack article from 2022.

At the end of the civil war (1967-1970), Nigeria enjoyed a windfall in petroleum profits. That funded the 1970s construction boom within Nigerian cities and some of the money was circulated to poorer countries in the West African subregion to buy goodwill. It didn’t take long for Nigeria to create Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) via the Treaty of Lagos (1975) to integrate the countries of West Africa under its leadership.

During the Cold War, Nigeria set its sights even higher. It gave scholarships and diplomatic papers to black South Africans fleeing the apartheid regime. The apartheid regime did not recognize black South Africans as citizens and so refused them passports. Nigeria along with other African states issued travel documents and, sometimes, granted citizenships and passports.

Nigeria also gave weapons to the Namibians and Zimbabweans, though not on the gigantic scale of China and USSR. The future President of post-apartheid South Africa, Mr. Thabo Mbeki, lived in the city of Lagos in the 1970s as an exiled anti-apartheid activist at Nigerian government expense. Other ANC exiles in Nigeria enjoyed similar perks and their children did not pay school fees while Nigerian citizens had to pay for their own children’s education.

ECOWAS struggled with economic integration due to huge disparities in sizes of national economies and political instabilities within its member-states, including Nigeria itself.

Nevertheless, under Nigeria’s guidance, the organisation has made some positive strides and expanded from a purely economic organization to one with a mission of greater regional integration in the political, security, educational and cultural spheres.

Free movement and ability to gain residency across all ECOWAS member-states has since been instituted. So a Ghanaian can enter Nigeria without visa and vice-versa.

There is the West African Gas Pipeline network commissioned in 2006 to supply Nigerian natural gas to smaller member-states, Benin, Togo and Ghana for various purposes, including power generation, industrial use, and domestic consumption.

There are international road networks connecting these member-states to each other, courtesy of Chinese construction companies. In the distant future, I am certain that there would railroads connecting the various member-states. After all, many African countries, including Nigeria, are busy expanding existing railway networks or constructing brand new ones.

Within Nigeria, the federal government and some state governments are implementing their own separate railway projects. A few months ago, I wrote about the Lagos Metro Rail, an intra-city railway network being constructed for Lagos State.

In the educational sphere, ECOWAS integration has only partial success. Anglophone member-states of the organisation are well-integrated due to the pre-existence of standardized West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) for teenagers graduating from secondary schools. Whether you are from Sierra Leone, Ghana or Nigeria, you take the same examination and earn the same certificate, which is internationally recognized as a valid entry requirement for further education anywhere in the world.

The West African Examination Council (WAEC), which has been conducting standardized WASSCE in Anglophone West Africa since 1952, has plans to incorporate French-speaking ECOWAS member-states into its examination system. But incompatibilities between the educational systems of Anglophone and Francophone countries remains a big stumbling block.

At the moment, WAEC administration of WASSCE in Francophone members-states is restricted to private candidates and secondary schools following academic curricula similar to those of Anglophone West Africa.

Moves to get the separate armed forces of all ECOWAS member-states to work together began with the signing of the Protocol on Mutual Defence Assistance on 29 May 1981.

However, the whole idea of military intervention in politically unstable member-states was a result of the First Liberian Civil War (1989-1997), which was trigged by political instabilities resulting from the 1980 military coup that ended 133 years of Americo-Liberian rule.

Liberia’s origin begins with American abolitionists establishing a voluntary repatriation zone for freed Black American slaves in 1820. Those freed ex-slaves eventually took control and declared that zone the independent Republic of Liberia in 1847 and named their capital city, “Monrovia” to honour US President James Monroe who had backed the mission to establish a settler state for Black Americans in West Africa.

The freed Black American slaves that were settled in the territory now known as Liberia never got on with the indigenous Africans who were not consulted about the settlement of “outsiders” on their homeland.

United States Navy had to intervene multiple times to suppress insurrections carried out by indigenous Africans against the unwelcome Black American settlers, in 1821, 1843, 1876, 1910, and 1915.

Over time, resettled Black Americans and their descendants—as well as a tiny Caribbean immigrant minority— came to be known as Americo-Liberians.

The feeling of dislike between the natives and Americo-Liberians was mutual. When the Liberian republic came into existence in 1847, the indigenous Africans were denied citizenship rights despite constituting 95% of the national population.

Americo-Liberians were able to preserve their distinct identity through endogamous marriages. The light-skinned ones of mixed race were quite particular about not “tainting the lineage with racially inferior natives.” Quite hilarious when one realizes that they had experienced similar treatment in the USA, their country of origin. The dark-skinned ones were no better.

However, it is important to state the practice of endogamy had begun to slowly decline among Americo-Liberians long before the 1980 coup.

From 1847 to 1963, most of the indigenous population did not have the right to vote or stand for elected office in Liberia. Even the 1963 extension of the franchise was done reluctantly.

Back in 1927, the League of Nations had condemned the Liberian government for discriminating against the indigenous people and selling them as “slaves” and “forced labourers”.

The bloody coup d'état of 12 April 1980 in Liberia was extraordinarily unusual in Africa because no commissioned military officers were involved in it. That was because, at that point in history, many indigenous African soldiers in the Liberian Army were relegated to the lowest rungs of the military hierarchy.

The bloody coup, carried out by enlisted soldiers, was led by 18 non-commissioned officers (NCOs), all indigenous Africans. President William Tolbert, an Americo-Liberian, was murdered along with 27 supporters. His son, Benedict Tolbert, was also killed.

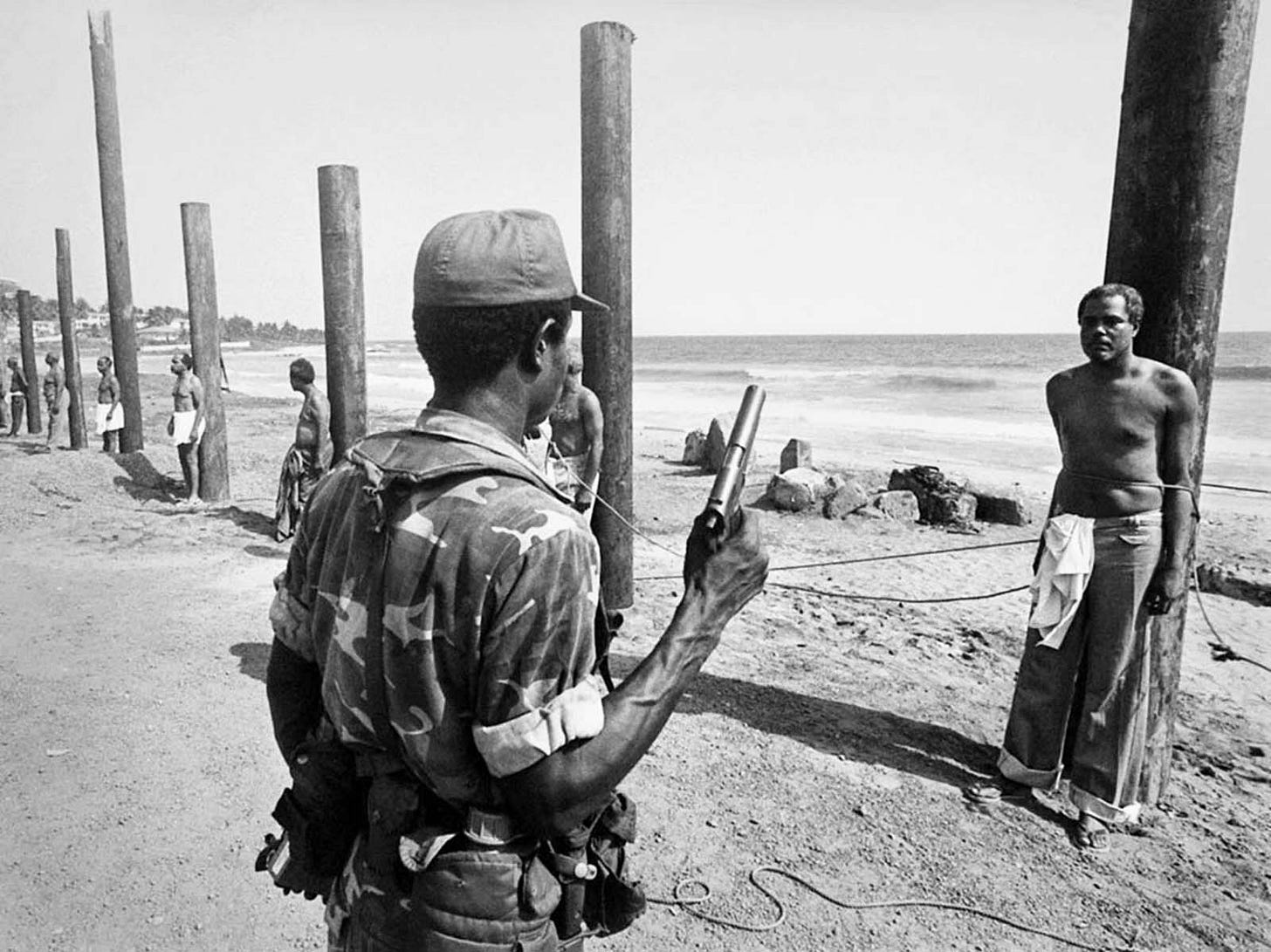

Ten days later, 22 April 1980, more detained Americo-Liberian public officials were paraded semi-nude on the streets and then executed by firing squad while teeming crowds of indigenous Africans cheered with joy.

Little did those joyful spectators watching mass murder realize that political instability would follow and then two bloody civil wars (1989-1997 and 1999-2003) that cost thousands of lives. The First Liberian Civil War would see the first widespread use of young children as gun-totting irregular fighters in Africa.

In spite of everything I have stated above, tensions between Americo-Liberians and indigenous Africans were declining prior to the 1980 coup. Some inter-marriages had taken place in the previous decades. President William Tolbert’s wife was of partial indigenous origin. Despite brief episodes of civil unrest, the country was generally stable, albeit very poor.

The 1980 coup d'état not only brought an end to 133 years of Americo-Liberian rule, it also shattered over a century of political stability.

Ironically, the putschists, who aimed to rectify historical injustices, inadvertently laid the foundation for the destabilization of the country. Once in power, the coup leaders awarded themselves and others the military commissions long denied to them by the Americo-Liberians.

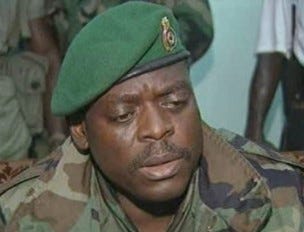

The new military ruler of Liberia, Samuel Doe, promoted himself from Master-Sergeant to “General”. His subordinates did the same.

Following the historic trajectory of almost every African state that has ever experienced a coup d’état, the Liberian military junta would endure several failed attempts by disgruntled/ambitious soldiers to remove it from power. To safeguard itself, the junta would take severe measures to suppress and eliminate both internal and external critics.

The first victims were five left-leaning members of the junta led by deputy military ruler Thomas Weh Syen who had assumed the rank of a “Major-General” after the 1980 coup. He and four others had criticized the forced reduction of Soviet Embassy staff from 15 to 6 and the outright closure of the Embassy of The Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Republic.

All five critics were purged from the junta and arraigned for a three-day sham trial for conspiracy to “overthrow the government with finance from Gaddafi.” They were executed by firing squad on 15 August 1981.

In 1983, Sergeant Thomas Quiwonkpa, who had also adopted the rank of a “Major-General”, expressed unhappiness with the ruling junta and was immediately purged. In November 1985, he attempted to overthrow the junta. It failed and he was killed.

Since Thomas Quiwonkpa was ethnic Gio (also called “Dan”), the Liberian military junta began a pogrom against ordinary people who happen to be ethnically Gio or belonged to the similar Mano ethnicity.

With funding from Gaddafi’s Libya, Mr. Charles Taylor, an Americo-Liberian fugitive sought for embezzling public funds, returned home to organize insurgency among the indigenous peoples belonging to the Gio and Mano ethnicities. The opening shots for the First Liberian Civil War cracked on 24 December 1989.

At the time, ECOWAS had no protocols for military intervention and so limited itself to trying to persuade Liberian Head of State Samuel Doe to resign and go into exile. Doe refused and eventually paid with his life on 9 September 1990. He was captured, tortured and murdered by insurgents who video-taped everything.

By August 1990, the civil war in Liberia was threatening to spread to neighbouring Sierra Leone and Guinea. Nigeria pushed other members of ECOWAS into agreeing to a military intervention.

That Nigerian-led intervention in Liberia set the precedent for future military action in other troubled member-states, especially after it was formalized as part of ECOWAS protocols to maintain regional security.

The Sierra Leone Civil War (1991-2002) began as a spill-over from the First Liberian Civil War. On 25 May 1997, while the war was raging, the Sierra Leonean Army overthrew the elected civilian President Ahmed Tejan Kabbah, who then fled the country.

The coup d'état that installed Major Johnny Paul Koroma as the military ruler in Sierra Leone wasn’t bloody. In fact, most coups in Africa’s history aren’t as messy as that of Liberia. But it did not really matter because the results of these coups—bloody or not— are generally the same.

The political chaos created by the 1997 military coup in Sierra Leone caused the death squads, some whom have come from neighbouring Liberia, to gain control of most of the country—something they had not managed to achieve in the previous six years of fighting government troops.

Gaining access to the rest of the Sierra Leone allowed the death squads to industrialize their massacres of hapless civilians and maximize the number of children with chopped off arms and hands.

These sadistic death squads— otherwise known as “Sierra Leonean rebels”—were witty enough to allow captured adults and children to choose between a “long sleeve cut” and a “short sleeve cut”. The choice of a “short sleeve cut” meant having your hand hacked off. “Long sleeve cut” translates to having the entire arm chopped off.

As the situation inside Sierra Leone continued to deteriorate, Nigeria’s army, navy and air force— acting unilaterally in the name of ECOWAS— intervened in June 1997 to reverse the coup, restore exiled President Kabbah back to power, and fight the crazed Sierra Leonian rebels.

Over the years, Nigerian-led troops would go on to intervene in several ECOWAS member-states experiencing political instabilities as mentioned earlier in this article.

3. FRENCH RELATIONS WITH NIGERIAN-LED ECOWAS:

French relations with ECOWAS has always had its ups and downs, depending on the temperament of the personality occupying the office of the President of France. Leftwing or rightwing political beliefs had almost no effect on the behaviour of personalities occupying Elysée Palace.

Aside from the temperament of the presidential office-holder, the only other factor that ever affected French behaviour in Francophone Africa were practical realities and changing geopolitical interests.

Presidents Charles De Gaulle, Georges Pompidou, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, François Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac were protective of La Francafrique system developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s to maintain French control of Francophone African states when it became politically impossible to continue administering them directly as colonies in the face of strong pressure from the United Nations (UN).

At the time, France was constantly being harried by UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld to follow the example of the British who were willingly and successfully liquidating their African colonial empire (except in South Africa and Southern Rhodesia where local white settlers put up fierce resistance).

The French colossus, General Charles De Gaulle, was the national leader who oversaw the successful transformation of the colonies into nominally independent client states of France through formal accession to Communauté Française, which was falsely presented to the world as a free association of sovereign states similar to European Economic Community (EEC).

In practice, that supranational entity was nothing like the EEC. Moreover, by January 1961, France was already bypassing Communauté Française to exercise direct influence on its client states via the neocolonial La Francafrique system built by Jacques Foccart who was Charles De Gaulle’s Chief Adviser on African Affairs.

In the run up to decolonization process in the late 1950s, which France had reluctantly agreed to implement under UN pressure, Jacques Foccart was tasked with laying the groundwork for the nascent neocolonial system.

He built up a network of comprador elites in each of France’s colonies. Many of these future ruling elites would be drawn from a small group of French-educated Africans, some of whom had served in the armed forces, civil service and parliament of France. Two notable examples are Flight Captain Albert-Bernard “Omar” Bongo of the French Air Force and Félix Houphouët-Boigny, an African legislator in the French Parliament.

After nominal independence in 1960, Houphouët-Boigny became President of Ivory Coast. With the encouragement of Jacques Foccart, Flight Captain Bongo became a part of the national government of Gabon in 1960. His retirement from the French Air Force followed shortly.

Bongo’s rise through the hierarchy of the extremely Francophile Gabonese government was rapid. By November 1966, he was Vice-President of the country, and then the President in December 1967.

Where strong opposition to La Francafrique was encountered, assassination promptly followed. Marxist-leaning Cameroonian politician, Ruben Um Nyobé, who tried to foment an armed revolt, was shot dead by French troops on 13 September 1958. Another radical Marxist Cameroonian politician, Félix-Roland Moumié, was finished off in exile with thallium poison by SDECE (then the French Secret Service) on 3 November 1960.

The SDECE, infested with Corsican gangsters, did not limit itself to assassinating Marxists. It also killed nationalist African politicians who would not go along with La Françafrique.

For opposing French influence in Morocco, Mehdi Ben Barka, a Moroccan nationalist politician, disappeared forever on 29 October 1965. His fate remained unknown until a book, published in 2018, by Israeli journalist Ronen Bergman, gave a detailed account of what had happened to him. According to the book, Mossad had assisted SDECE in Barka’s murder and the disposal of his body.

The colony of Guinea represented an abject failure for Jacques Foccart. Its principal leader Ahmed Touré refused to cooperate. He stood as the sole Francophone African national leader who opposed the notion of joining the Communauté Française and rallied Guineans to vote for complete independence from France in the referendum held on 28 September 1958.

As I reported here and here, France retaliated by destroying most of the infrastructure it had built on Guinean territory before pulling its colonial administrators, technocrats and military troops out. Thereafter, the abandoned rebel colony declared itself a sovereign nation on 2 October 1958, making it the first francophone sub-Saharan African nation to do so. It was also the first to drop the CFA Franc as currency after independence, and the first not have any French troops on its territory.

The SDECE made repeated attempts to assassinate Ahmed Touré, but none were successful. In fact, the end result of those botched assassination attempts was Guinea’s shift from having strained relations with France to having zero relations with France for many years.

Meanwhile, the Soviets deepened their ties with Ahmed Touré and sent multiple naval ships to patrol the waters of Guinea to deter Portuguese troops based in neighbouring Guinea-Bissau from repeating Operation Green Sea (1970). Touré had angered Portugal by allowing his country to be used as rear bases for armed guerillas fighting for the liberation of the Lusophone colonies of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Islands.

With the sole exception of the Republic of Guinea, Jacques Foccart succeeded in the objective of maintaining French control over Francophone Africa.

However, in West Africa, there was a fly in his ointment, a seemingly intractable problem—that is, until a fortuitous solution presented itself some years down the line. That problem was called Nigeria.

Charles De Gaulle bemoaned the fact that Anglophone Nigeria existed in a corner of Africa where French-speaking states were in the majority. Nigeria had the largest population of any country on the continent.

Back then, Nigeria had an agrarian economy, which was growing very fast in the early 1960s. Vast reserves of petroleum resources was discovered in 1958, but did not play a strong part in Nigeria’s economy until the 1970s.

Given its gigantic national population and large economy, De Gaulle correctly predicted that Nigeria would eventually become the hegemon of West Africa and France would be powerless to do anything about it as it exercised zero influence in Anglophone Africa. Moreover, France’s commercial trade with the landlocked Francophone states of Niger and Chad relied heavily on the transit through the territory of Nigeria and the use of its sea ports.

The federal government of newly independent Nigeria vocally opposed continued French control of Algeria, supported the defiance of Ahmed Touré in Guinea, and expelled the French Ambassador to Nigeria in January 1961 to protest France’s third nuclear bomb test in the Sahara Desert on 27 December 1960.

The expulsion of the French Ambassador was followed by the closure of all Nigerian sea ports and airports to French ships and aeroplanes, but those measures were soon reversed after the economies of landlocked Chad and Niger were adversely affected. The French Ambassador was not allowed to return to Nigeria until 1965.

Despite, its robust foreign policy of backing African peoples still struggling against recalcitrant colonial powers—Portugal in all its colonies and France in Algeria—there were still a myriad of internal political problems within post-independence Nigeria. A lot of those problems stemmed from its status as a heterogenous federation of 250 ethnic nationalities that spoke mutually unintelligible languages and followed different cultural traditions and religions.

Long before independence day arrived in 1 October 1960, the ethnic Hausa-Fulani Muslim ruling elites of Northern Nigeria were wary of Christian Southerners, especially the ethnic Igbos of Southeast Nigeria.

Starting in 1914, thousands of Southerners migrated to the Northern Nigeria after the British colonial authorities opened up the conservative Muslim region with the construction of railway lines. The vast majority of those Southern immigrants in the North were ethnic Igbos who had come to take up jobs as railway drivers, craftsmen and traders.

By the 1950s, Igbos resident in Northern Nigeria had done well for themselves as traders, doctors, engineers and teachers. Nevertheless, as non-Muslims, they were compelled to live apart from the native peoples in segregated sections of Northern cities and towns known as Sabon Gari.

The British colonials did not interfere with the pre-existing local custom of segregating non-Muslim immigrants from the Muslim natives because of the autonomy granted to local Emirs (traditional rulers) to govern the Northern part of the British Protectorate of Nigeria.

In pre-colonial times, those Emirs had been in charge of Emirates (provinces) that made up a monarchial sovereign state known as Sokoto Caliphate (1804-1903).

The sovereign territory of this extensive Sunni caliphate now encompasses present-day Northwest Nigeria, Southern Niger, and small portions of Cameroon, Burkina Faso, and Benin Republic.

The caliphate was conquered and partitioned by British, French and German colonial empires in March 1903.

The British quickly absorbed its own share of the conquered territory into the newly formed Northern Nigerian colony, which also included the former territories of defunct Kanem-Bornu Empire (926-1846).

The British colonials came to an amicable arrangement with the local Emirs. They would be allowed to continue governing the Emirates, which had survived the dissolution of the caliphate. The Brits would also do their best to keep Christian missionaries away from their provincial territories. In return, the Emirs would pledge loyalty to Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, and collect taxes for the British colonial administration. (Victoria had been dead for two years when the out-of-date accession documents prepared in her name earlier in 1897 were finally signed on 13 March 1903 by the Emirs).

Until the 1950s, Southern Nigeria, where the British had encountered fierce anti-colonial resistance, was not allowed any kind of self-governing autonomy. British colonial officers administered it directly.

So, it was no shock that most of the nationalists who favoured the end of colonial rule were Southerners. Northern leaders were not initially keen on decolonization because they feared that post-independence Nigeria would become a unitary nation-state under the dominant control of Southerners.

The Brits were not going to grant independence to Nigeria unless Northern leaders gave their consent. Attempts by Southern nationalists to secure national independence in 1954 was vetoed by the most powerful leader of Northern Nigeria, Sir Ahmadu Bello.

SIDE BAR: AHMADU BELLO ON ETHNIC IGBOS RESIDENT IN THE NORTH

Before his assassination, Sir Ahmadu Bello (1910-1966) was the most powerful politician in the autonomous region of Northern Nigeria and its ruling Premier during the final phase of British colonial rule (1954-1960) and after independence (1960-1966). Prior to becoming Premier, he was an elected legislator in the Northern Nigeria House of Assembly.

He was the great-grandson of Muhammad Bello who ruled the Sokoto Caliphate from 1817 to 1837. He was also the great-great grandson of Usman Dan Fodio, the founder of the caliphate and its ruler from 1804 to 1817.

Like many Northerners of his time, Premier Ahmadu Bello had a deep animus towards the ethnic Igbos, which he was not shy of expressing when prompted by local and foreign journalists.

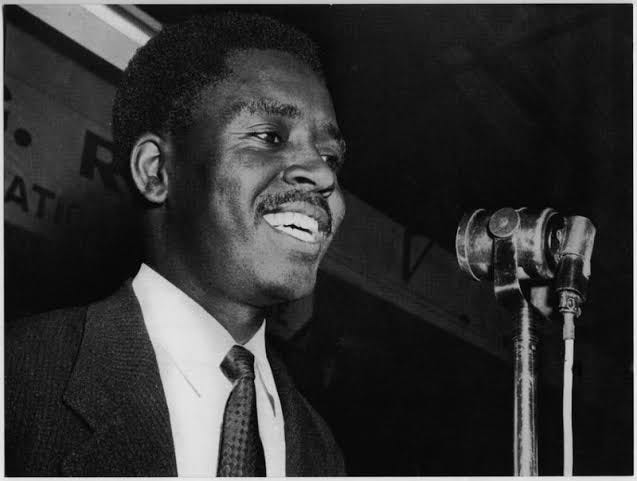

In a television interview with a British journalist, recorded on 19 April 1964, Ahmadu Bello, in his capacity as the Premier of Northern Nigeria, expresses concerns about the highly ambitious Igbo “who attempts to become the boss after a brief period as the servant.”

During the interview, Bello explains that the policy of his regional government is to discriminate in favour of Northerners when offering job opportunities. Just like expatriates of foreign countries, all Southern Nigerians (including ethnic Igbos) resident in the North can only get temporary work contracts.

Bello’s claims to the journalist that Northerners hardly get jobs in the other two autonomous regions (Eastern Nigeria and Western Nigeria) isn’t true as neither of them followed any policy of discrimination against non-native peoples resident on their territories.

It was the absence of discriminatory policies that allowed a Northern Muslim resident of Eastern Nigeria, Mr. Umaru Altine, to join local politics and stand in regional elections. From 1952 to 1958, Umaru was the popularly elected mayor of Enugu city, the administrative capital of Eastern Nigeria.

In 1957, Ghana made history as the first British colony in Sub Saharan Africa to gain full independence. Meanwhile, Nigeria remained a partial self-governing colony because its local political leaders were still bickering over the structure of a future independent state.

As a compromise, Southern leaders, who desperately desired independence, were eventually compelled to drop the idea of a unitary nation-state in favour of a federation that would protect the autonomy of Northern Nigeria. A new federal constitution was written and Nigeria finally gained independence in 1960. At the time, it was one of only two African countries with federal systems of government, the other one being Ethiopian–Eritrean Federation (1952-1962).

After independence, tensions emerged among the three largest ethnic nationalities in Nigeria, namely the Igbos, Yorubas, and Hausas. Moreover, within their respective home regions, each of these major ethnic groups encountered tensions with resentful ethnic minority populations.

Ethnic minorities in Igbo-dominated Eastern Region demanded their own separate administrative region. When that was not forthcoming, Ijaw ethnic minority militants led by Isaac Adaka Boro declared a “Niger Delta Republic” on the territory of Eastern Nigeria in 1965 and fought Nigerian federal troops for twelve days before he and his men were defeated.

Ethnic minorities in Yoruba-dominated Western Region also campaigned for a separate administrative entity to be called Midwestern Region, and succeeded in June 1963.

Ethnic minorities—who also happened to be Christian minorities— in the ethnic Hausa Muslim-dominated Northern Nigeria demanded the creation of a Middle Belt Region. When that was not forthcoming, these minorities rioted and the Hausa ruling elites cracked down hard, arresting minority rights leaders such as Joseph Tarka.

Fed up with government corruption and petty ethnic nationalisms, a group of middle-ranking military officers led by left-leaning Major Chukwuma Nzeogwu staged a bloody military coup d'état on 15 January 1966, which resulted in the deaths of prominent Nigerian politicians, including Northern political leaders such as Ahmadu Bello and Abubakar Tafawa Balewa. The coup ultimately failed to achieve its objectives.

Instead, that military coup set off a long chain of tragic events that led to the 1966 pogrom of ethnic Igbos resident in the segregated Sabon Gari areas of Northern Nigeria. 30,000 Igbos were brutally murdered and a further one million fled to their Eastern homeland. Shortly after, an outraged Eastern Nigeria declared itself a sovereign nation—the Republic of Biafra.

The Northern-dominated Nigerian military junta, which seized power in August 1966, refused to recognize the secession of what it still considered its Eastern Region. In July 1967, Nigeria attacked Biafra, triggering the civil war (1967-1970).

On the international scene, a lot of unexpected things happened. The Soviet Union and most of its communist East European satellite states joined the United Kingdom in supporting Nigeria. The British and the Soviets competed with each other on who would pile Nigeria with the most military equipment.

Czechoslovakia was sympathetic to Biafra and covertly supplied weapons to the secessionist republic at the early stages of the civil war. All of that ended with the Soviet-led Invasion of Czechoslovakia (August 1968), which crippled the reformist government of Alexander Dubček. After that invasion, Czechoslovak weapons flowed exclusively to Nigeria in accordance with Soviet wishes.

Nigeria also received the backing of most African countries. Egyptian Air Force personnel were sent to pilot MIG-17 jet fighters and Ilyushin Il-28 jet bombers supplied to Nigeria by the Soviet Union since Nigeria’s ethnic Igbo pilots, training for the nascent Nigerian Air Force, had all defected to the Biafran Air Force.

China voiced sympathy for the plight of Igbo victims of the 1966 pogrom and declared its support for Biafra while denouncing what it called “Anglo-Soviet Imperialism”. Norway also its voiced sympathy too and donated relief materials for internally displaced Biafrans during the civil war.

The United States was too busy with the raging Vietnam War to form a coherent policy on the Nigeria-Biafra conflict. The administration of President Lyndon Baines Johnson declared the neutrality of USA.

The Catholic countries of Europe—Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Italy and The Vatican— were all sympathetic to Biafra since the vast majority of Biafrans were Catholics, including the future Cardinal Francis Arinze, who made history as the youngest Catholic bishop in the world when he was consecrated on 29 August 1965, at the age of 32. (Italy’s sympathy for Biafra waned after some Biafran soldiers killed Italian AGIP workers in 1969).

Israel also backed Biafra and joined China and Portugal in the clandestine supply of weapons to the secessionist state.

Tanzania, Zambia, Ivory Coast and Gabon broke ranks with the rest of Africa and granted diplomatic recognition to Biafra. The Caribbean nation of Haiti soon joined with its own recognition of Biafra.

Meanwhile, back in Paris, Jacques Foccart was rubbing his hands together. He could not miss a golden opportunity to finally do something about the gigantic Nigeria, which was overshadowing the much smaller Francophone states in West Africa.

Jacques Foccart enlisted the help of Ivorian President Félix Houphouët-Boigny in a bid to persuade a reluctant President Charles De Gaulle to declare that France would recognize Biafra as a sovereign state.

De Gaulle had no love for the Nigerian Federation. He had not forgotten how Nigeria humiliated France in January 1961 by expelling the resident French Ambassador and banning French commercial operations from using Nigerian sea ports and roadways to reach landlocked Niger and Chad. Nevertheless, he had no wish to offend British Prime Minister Harold Wilson who was fully committed to backing the Nigerian military junta’s scorched-earth war strategy of forcing the Biafrans back into the Nigerian Federation.

Jacques Foccart told the ageing French President that supporting Biafra’s independence would mean Nigeria’s loss of access to vast petroleum reserves inside Biafra. Foccart theorized that the loss of such critical natural resource would slow down the economic growth of Nigeria, which also stood to lose 8.4% of its landmass, 26% of its population and a large portion of its coastline if the partially recognized Biafran republic won the civil war.

De Gaulle stubbornly stuck to his refusal to recognize Biafra, but he authorized the supply of military equipment to the Biafrans. Jacques Foccart went far and beyond his mandate. He supplied both weapons and recruited French, German and Belgian mercenaries to fight alongside the conventional armed forces of Biafra. Some of these mercenaries would eventually be expelled for refusing to follow the orders of the Biafran military high command.

Unfortunately for Biafra, the Nigerian military junta maintained a merciless air, land and sea blockade that caused a humanitarian crisis and made it extremely difficult for the Biafran Armed Forces to receive smuggled weapons from China, Tanzania, Portugal, Israel and France.

In response to the blockade, Biafra developed cottage industries to make some of those weapons locally, but production levels were never enough to match the enormous numbers of far more sophisticated weapons that the Brits and the Soviets lavished on Nigeria.

On 15 January 1970, the Biafran Armed Forces surrendered to Nigeria and the Biafran republic ceased to exist, its territory reverting to its pre-war status as Eastern Nigeria.

For a long time, relations between Nigeria and France was on ice. Meanwhile, Nigeria’s petroleum revenues rose sharply, especially during the Arab Oil Boycott (1973), which caused international crude oil prices to soar. Nigeria made a killing from petroleum sales and the revenue drove a construction boom in the major cities.

Nigeria began to circulate some of the oil money to poorer African countries, especially in the West African subregion. Nigeria used some of money to purchase weapons that were airlifted to Zambia, which then passed them to Joshua Nkomo’s ZIPRA fighters and Robert Mugabe’s ZANLA fighters, both battling the unrecognized Rhodesian State. Some weapons made it to SWAPO guerrillas fighting the apartheid South African occupation army in Namibia.

Nigeria’s creation of ECOWAS in 1975 was not well received in Paris by French President Valery d'Estaing, who perceived it as attempt by petroleum-rich Anglophone Nigeria to compete with France for influence in Francophone West Africa. Nevertheless, Valery did nothing to impede ECOWAS. With the passage of time, it dawned on him that ECOWAS was mostly a trade organisation, which did not necessarily challenge La Francafrique.

Nigeria was keen on building a large regional trading bloc of all 16 countries in West Africa, but never concerned itself with fighting France over its insistence on controlling the currency and fiscal policies of some Francophone member-states.

SIDE BAR: THE CURRENCIES KNOWN AS THE CFA FRANC

The CFA Franc, which is partly managed by the French Treasury, has been identified as one of the tools used by France to advance its influence and control of some of its former African colonies. While, that assertion has been largely true, there are important bits of nuance to be explored.

Out of twenty former French colonies, twelve use the CFA Franc. Additionally, two African countries— which were never French colonies— voluntarily dropped their own national currencies in favour of the CFA Franc.

Contrary popular belief, the CFA Franc is not a single currency, but rather the common name of two separate currencies issued by two different central banks.

West African CFA Franc is the currency of eight West African countries, which consists of seven Francophone states (Benin Republic, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo) and one Lusophone state (Guinea-Bissau).

After years of economic problems and high inflation, Portuguese-speaking Guinea-Bissau dropped its own national currency (Guinea-Bissau Peso) and voluntarily adopted West African CFA Franc in 1997. Of course, it is deeply ironical that Guinea-Bissau— which extracted its independence from Portugal after 11 years of warfare—ended up surrendering its national fiscal policy to the French Treasury through voluntary admission to the CFA Franc Zone.

The Central African CFA Franc is used by six central African countries— one former Spanish colony (Equatorial Guinea) and five former French colonies (Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Gabon and Republic of the Congo)

Spanish-speaking Equatorial Guinea voluntarily ditched its national currency (known as Ekwele) on 1 January 1985 and adopted the Central African CFA Franc in order to stabilize its economy and ease trading with other countries in the Central African subregion.

As stated earlier, each version of the CFA Franc is issued by a separate central bank. West African CFA Franc is issued by the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) while Central African CFA Franc is served by the Bank of Central African States (BEAC).

Originally, both banking institutions were 100% controlled by France and headquartered in Paris. However, growing criticism of the quasi-colonial “La Francafrique” system in the 1970s caused France to grant African countries in the CFA Franc Zone a greater say in the management of both banks. The headquarters of both banks were also relocated to the African continent.

In 1975, BCEAO got its first African bank governor, Mr. Abdoulaye Fadiga of Ivory Coast, and its headquarters moved from Paris to the city of Dakar, Senegal in 1978.

Its sister entity, BEAC, transferred its headquarters from Paris to the city of Yaoundé in Cameroon in 1977. The following year, BEAC got its own pioneer African governor in the person of Casimir Oyé-Mba, who later became Prime Minister of Gabon after he left the central bank.

Despite the relocation of headquarters, and the fact that both central banks have been administered by African governors for many decades, the French Treasury continued to dominate decision-making in both banking institutions.

Both variants of the CFA Franc have come in for a lot of criticism. It has been described as a “neocolonial tool” because each of the 14 African nations operating either version of the CFA Franc were historically required to deposit half of their foreign exchange reserves with the French Treasury.

Because both versions of the CFA Franc were pegged to the French Franc, the African countries using either currency could not exercise a sovereign right to set their own monetary policies. The duty of setting monetary policy for countries of the CFA Franc Zone was in the hands of Banque de France until 1 January 1999 when the Euro replaced French Franc as the pegging currency. Thereafter, monetary policy passed to European Central Bank, which is advised by the French Treasury on all matters concerning both CFA Franc currencies.

In spite of their drawbacks, some economists have argued that the 14 countries using either version of the CFA Franc have been able to avoid currency fluctuations, allowing them to enjoy a level of macroeconomic stability.

As evidence, these economists point to the fact that Republic of Mali dropped the West African CFA Franc in 1962 and began to mint its own currency—the Malian Franc— as a means of escaping French control of its monetary policy. However, after 22 years of operating a socialist-style economy, with attendant high inflation and currency fluctuations, Mali decided to dump the Malian Franc and reinstate the more stable West African CFA Franc as its national currency.

Guinea-Bissau and Equatorial Guinea—both of which are neither Francophone nor former French colonies—voluntarily dumped their own national currencies in favour of the more stable CFA Franc.

It would be remiss of me not to acknowledge the fact that Francophone Ivory Coast, using West CFA Franc, has been experiencing relatively low inflation at an average rate of 6% over the past 50 years compared to 29% in neighbouring Anglophone Ghana, which has proudly operated its own independent national currency since 1957. Of course, on the upside, Ghana does not have to worry about foreign control of its monetary policy.

Once initial suspicions of Nigeria wanting to erode French control in Francophone West Africa had receded, President Valery d'Estaing, and his successors, began to perceive ECOWAS as organization that could be influenced by Elysée Palace since nine out of its sixteen member-states were former French colonies.

Of course, French influence in Francophone West Africa was never uniform, even in the 1970s. Elysée Palace had no control over events inside Republic of Guinea, which had allied itself with the USSR. French influence over Mauritania continuously waxed and waned.

Mauritania rescinded its full membership of ECOWAS in December 2000 and returned as an associate member in August 2017.

With 56.3% of ECOWAS members being Francophone countries, it was generally assumed that they could always outvote the bigger Anglophone nations of Nigeria and Ghana on contentious issues in which France had a vested interest.

As the French would eventually come to realize over the years, Anglophone Nigeria held a de facto veto power over decision-making within ECOWAS. Nothing could be done by ECOWAS without the express approval of Nigeria. Francophone majority inside ECOWAS was not enough to move the needle if Nigeria stood in the way.

The transformation of ECOWAS in 1990 from a purely regional trade organization to one that also had a mandate to intervene in politically troubled member-states was not well-received by the socialist French President François Mitterrand and his rightwing successor, Jacques Chirac.

The heyday of La Francafrique system was from 1960 to 1990. Thereafter, it began to slowly decay due to French budgetary cutbacks, the retirement or death of key French people who ran the highly informal system of control and French integration into the European Union, which reduced dependence on trade with the former African colonies.

Under Jacques Chirac, the first visible sign of a weakening La Francafrique regime emerged. Waning interest in the highly unstable Central African Republic (C.A.R) led President Chirac to use the excuse of a minor spat with the normally Francophile C.A.R President Ange-Félix Patassé to voluntarily close the sole French military base there and withdraw all 1,400 troops in July 1997. Simultaneously, Chirac reduced troop numbers in military bases in Gabon, Ivory Coast, Senegal, Djibouti, Burkina Faso and Mali.

Despite all of this, France did not hesitate to intervene in the two civil wars that engulfed Ivory Coast following the political crisis that emerged after the death of Ivorian leader Houphouët-Boigny in 1993 and the 1999 Christmas Eve military coup, which worsened the chaos.

Still committed to preserving La Francafrique, President Chirac ordered the 650 French soldiers already inside Ivory Coast to intervene when the First Ivorian Civil War (2002-2007) broke out. These troops were later joined by soldiers from French military bases in other African states. Although Chirac declared the neutrality of France, both warring parties in Ivory Coast accused French troops of taking sides. In the end, French forces found itself fighting Ivorian rebels on certain occasions and Ivorian government troops on other occasions.