Certain publications have been alleged that the Sudanese conflict was instigate the Americans because they are annoyed with the Sudanese military regime for negotiating a deal that will allow Russia to site a military base near the African country’s Red Sea Coast.

Conversely, there have been Western media outlets (e.g. CNN International) which have alleged that it was Russia that instigated the conflict. This allegation hinges on the fact that the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitaries — at the behest of the now defunct Omar al-Bashir government—received training from Russian Wagner mercenaries several years ago.

I will say straight off the bat that both allegations are false. Neither Russia nor the United States of America are to blame for the violent conflict raging in Sudan.

The clash in Sudan is a purely domestic affair, the culmination of a series of events that finally caused the explosion of a decade-old gunpowder keg, which had been simmering in a slow burning fire since August 2013. I will be breaking it down here as we go along.

A lot has been made of US government representatives meeting with RSF paramilitary leaders before the violent clashes. What is not mentioned by anybody is that US government representatives also met far more often with the Sudanese military than it does with the rival RSF and have reaped many rewards and concessions from such contacts.

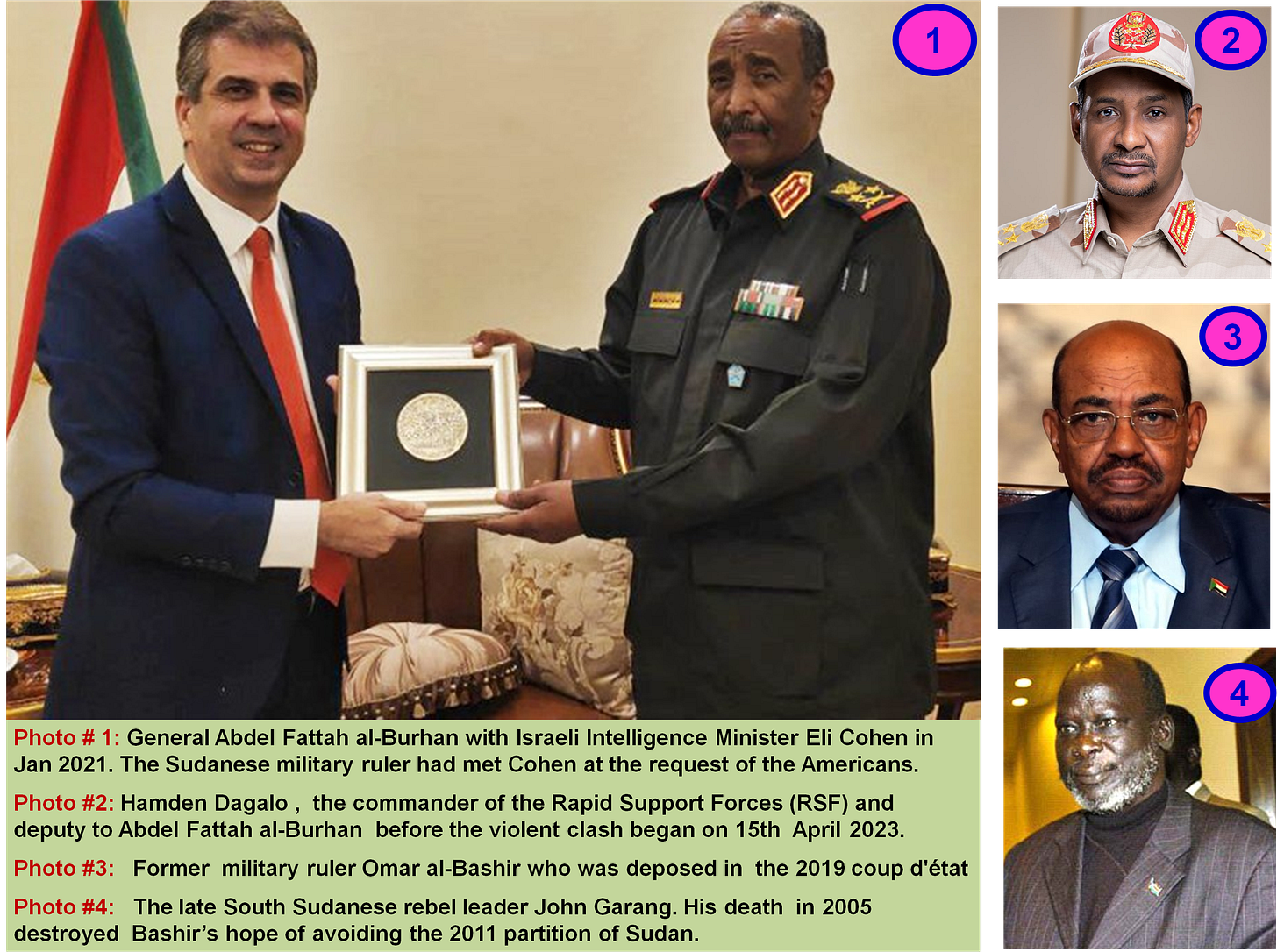

Such contacts persuaded the post-coup Sudanese civilian-military mixed regime to sign up to Abraham Accords brokered by the US government of then President Donald Trump in 2021. Further contacts with the US representatives resulted in the de facto Sudanese military ruler, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, holding a very public meeting, earlier this year, with Mr Eli Cohen who was Israeli Minister For Intelligence at the time.

The origin of the clash between the Sudanese armed forces and the RSF paramilitary can be traced all the way back to the Darfur War which broke out in 2003. The Darfur conflict itself is a fallout of the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), which resulted in the partition of the country on 9 July 2011.

Ever since Sudan achieved independence both from the United Kingdom and the now defunct Kingdom of Egypt on 1st January 1956, the various ethnicities that constitute the Sudanese citizenry have been at loggerheads.

The largest of these ethnicities was the Arabized Nubians, the caramel-coloured people usually referred to as “Sudanese Arabs”—a term I consider to be a bit of a misnomer given that these people aren't really Arabs; merely lighter skinned Africans who had been assimilated into Arabic culture and language.

I would also hasten to add that a handful of dark-skinned ethnic groups of Nilo-Saharan and Cushitic ancestry have also joined the caramel-skinned Nubians in claiming the “Sudanese Arab” identity.

Despite my misgivings about this “Sudanese Arab” terminology, I will use it for the purposes of this article.

The Sudanese Arabs constituted 40% of Sudan prior to its partition in 2011 and they effectively control all levers of power in the country. They run all government institutions at the national and regional levels and control the armed forces.

The remaining 60% of the population were generally darker-skinned Africans split into a multitude of ethnicities of various sizes spread unevenly across the territory of pre-partition Sudan, the largest single landmass on the continent of Africa.

The vast majority of the darker-skinned Africans lived in Southern Sudan and were mostly Christian. But there was a sizeable minority of dark-skinned Muslims who are native to Northern Sudan and do not claim the “Sudanese Arab” identity.

Regardless of religious faith, those darker-skinned ethnic groups tended to face varying degrees of discrimination from the lighter-skinned Sudanese Arab ruling elites.

The discrimination faced by dark-skinned South Sudanese ethnicities were particularly intense because they were largely Christians. That resulted in the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972), which ended with a peace agreement brokered by Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie.

The peace accord granted political autonomy to the South Sudanese and allowed the whole country to experience almost ten years of relative peace.

However, when a prominent Muslim Brotherhood leader, Hassan al-Turabi, was appointed Attorney-General of Sudan in November 1981, confidence in the national government collapsed across South Sudan.

The growing influence of the Muslim Brotherhood within the national government— which began in the late 1970s— had slowly manifested itself in discriminatory policies against non-Muslims. This discrimination hit its peak in 1983 when the political autonomy granted to South Sudan was revoked and Sharia law imposed across the entire country.

When the South Sudanese began a violent protest against these measures, the national government sent an army battalion down to the South to quell the unrest. Upon arriving in the South, the army battalion, entirely made up of South Sudanese soldiers led by Colonel John Garang, defected to the side of the protesters.

Days later, the national government declared a mutiny had occurred in the South and sent more military regiments to fight the protesters and Garang’s renegade soldiers. That singular event was the trigger for the Second Sudanese Civil War, which raged for 21 years and 7 months; making it one of the longest civil wars in the post-colonial history of the African continent, only surpassed by the Angolan Civil War (1975-2002).

By the early 2000s, the civil war had sunken into a stalemate, creating incentives for a peaceful settlement. Peace talks between South Sudanese rebels and the Sudanese government was still ongoing when a separate conflict broke out in a different part of Sudan in 2003.

This new conflict had the familiar hallmarks. It pitted the Sudanese Arab-dominated government of General Omar al-Bashir against an assortment of dark-skinned African rebels in the northwest region of Darfur. Unlike the Christian rebels of South Sudan, these new set of rebels in Darfur were as Muslim as the Sudanese Arab soldiers they were fighting.

Exhausted by years of fighting South Sudanese rebels, the national armed forces of Sudan was not in the greatest shape to fight this new separate war taking place in the northwest.

Unlike the South, the northwest region had huge expanses of desert and the army struggled to keep up with Muslim rebels of Darfur who drove rapidly across the sandy plains in pick-up trucks with machine guns mounted in the rear; an innovation that would have made the Ukrainian anarchist Nestor Makhno marvel at how things have changed since the days of the Tachanka (a horse-drawn cart with a heavy machine gun mounted in the rear, which was supposedly invented by Nestor).

In the vast expanses of northwest plains not patrolled by the Sudanese military, a private militia suddenly appeared to fight the muslim Dafuri rebels. This militia, known as the Janjaweed, was made up almost entirely of lightly armed Sudanese Arab civilians on horseback and was led by a man who sold camels for a living. His name was Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo.

Hamdan Dagalo’s private Janjaweed militia was arguably more effective in combating the Darfuri rebels than the war-weary national army of Sudan. However, Hamdan Dagalo's counter-insurgency operations was not limited to the muslim rebels in pick-up trucks, it extended to committing massacres against ordinary civilians who happened to share the same dark skin and ethnicities of the rebels. None of this bothered General Omar al-Bashir, the military ruler of Sudan from 1989 until his overthrow in 2019.

Bashir was thrilled that there was a private force out there, in the northwestern region, tackling these new rebels at a time when he was trying to make a peace deal with the South Sudanese and save the country from breaking apart. He gave his unalloyed support to Hamdan Dagalo's Janjaweed irregular forces and defended them against charges of war crimes against civilians.

For doing an effective job against the Darfuri rebels, Omar al-Bashir began to provide government funds and weaponry to the Janjaweed and its leader became a close friend of the Sudanese military ruler. Meanwhile, the national army, while appreciative of the efforts of the Janjaweed, was wary of the level of weaponry being lavished on the private militia. As far back as 2004, the Sudanese military high command urged caution, but Omar al-Bashir was not in the mood to listen.

In 2005, Bashir signed a peace deal with the South Sudanese, which stipulated that a referendum be held in six years to determine whether the South should secede or remain part of a united Sudan.

The Sudanese military high command was against any referendum on partitioning the country, but Bashir did not listen. He was firm in his conviction that the South Sudanese will vote in the future referendum to remain part of a united Sudan. And he had good reason to believe that.

The most powerful South Sudanese rebel leader, John Garang, was a staunch believer in a united Sudan and had coined the word “Sudanism” to define a set of ideas on how a united, post-war Sudan should be governed with equal citizenship rights for all Sudanese regardless of religion, ethnicity and region of origin.

Upon signing the 2005 peace deal, Bashir did the following: (1) he elevated John Garang to the position of Vice President of Sudan; (2) he reserved 20% of national government jobs for the South Sudanese; (3) he restored the Autonomous South Sudan Region abolished in 1983 with all rights to exploit its own petroleum resources and maintain a military force separate from the national armed forces of Sudan.

Bashir's dream of preserving Sudan as a united country was dashed when John Garang died in a helicopter crash on 30th July 2005 while visiting neighbouring Uganda. The late South Sudanese leader had been Vice President of Sudan for only three weeks before his death.

Another South Sudanese leader, Mr. Salvar Kiir, became the Vice President of Sudan on 11th August 2005. Unlike John Garang, he was dismissive of the concept of “Sudanism” and quickly declared his intention to seek the full independence of the Autonomous South Sudan Region in the upcoming 2011 referendum.

Meanwhile, the separate war in the northwest region between the Muslim Sudanese Arab government and the Muslim rebels of Darfur continued unabated. Hamdan Dagalo’s Janjaweed became more powerful with the support of its benefactor, President Omar al Bashir.

In 2009, Bashir was indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for “genocide” allegedly committed by the Janjaweed private militia, which he was backing. Although, I will have to say that the ICC charges had more to do with Bashir’s enemity with the United States than with anything the Janjaweed fighters may have done.

In 2011, South Sudan became an independent country, radically changing the ethnic demography of the rump federal state of Sudan. The size of the Sudanese Arab ethnicity jumped from 40% in the pre-partition population to 70% in the shrunken post-partition population. Keeping a hold of the troubled northwestern region became a massive priority for the rump state.

The year 2013 is key because it was when the private militia known as the Janjaweed suddenly became the core of a new government paramilitary called the Rapid Support Force (RSF), which was tasked with destroying the Darfuri rebels.

Despite having neither formal education nor any military training, the civilian leader of the Janjaweed militia, Mr. Hamdan Dagalo, was proclaimed a “Brigadier-General” of the newly created RSF by his friend and benefactor, President Omar al-Bashir. The professional Sudanese military was horrified.

That event completed the breakdown of the relationship between Bashir and top military brass, which started with his agreement to allow a South Sudanese referendum.

Fearing that the Sudanese military might overthrow him, Bashir began to build up the Rapid Support Force (RSF) as an alternative army that will be loyal and protect him from any coup d'etat.

By 2018, the RSF paramilitary was barely recognizable from its previous incarnation as the Janjaweed militia. Whereas the Janjaweed was composed mainly of lightly armed men on horses and camels, the RSF was equipped with howitzers, mortars, helicopter gunships, and tracked-wheel armoured tanks.

When Mohammed Bin Salman reached out to Sudan for help in fighting the Houthi fighters of Yemen, President Omar al Bashir did not bother to speak to the Sudanese Army. He spoke with his friend, Hamdan Dagalo, now a “Lieutenant-General”, who immediately agreed to dispatch 6000 RSF paramilitaries to assist the Saudi invasion forces in Yemen.

Hamdan Dagalo was obliged to do whatever Bashir asked because he had become an extremely rich man under the patronage of the Sudanese military ruler. With Bashir's acquiescence, Dagalo had used his RSF paramilitary to commandeer a gold mine and rapidly became the country's biggest gold trader.

When popular protests against the Bashir regime broke out in December 2018, Hamdan Dagalo was firmly on the side of his benefactor. The RSF paramilitaries came on to the streets of Khartoum city to beat protesters and spray tear gas all around.

On 11 April 2019, the Sudanese Army led by Lieutenant-General Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf declared that Omar al-Bashir was no longer President of Sudan.

Hamdan Dagalo loved Bashir, but he was not about to go down with his benefactor. He quickly switched sides and used his RSF paramilitary force to arrest and detain Omar al-Bashir.

Dagalo's switch of loyalties prevented what could have been a violent clash between the Sudanese armed forces and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) after Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf declared the end of the regime of Omar al-Bashir.

While the Sudanese top military brass still wanted RSF to cease to exist as an independent entity, the switch of loyalties by the paramilitary force was greatly appreciated and was rewarded.

For betraying his former benefactor, Hamdan Dagalo was integrated into the “transitional military council” that took power after the removal of Omar al-Bashir. The coup leader, Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf, headed that military junta for just 24 hours before he was compelled to step down in favour of General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who was subsequently acknowledged internationally as the de facto military ruler of Sudan.

Following a new constitutional charter negotiated with civilian politicians, the “transitional military council” was dissolved in August 2019 and replaced with a civilian-military mixed regime in which power was shared between General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Lieutenant General Yasir al-Atta, Lieutenant General Shams al-Din Khabbashi, RSF paramilitary leader Hamdan Dagalo and a group of civilian politicians led by Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok.

Rather than honour an agreement to step down as de facto head of the civilian-military mixed regime, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan carried out a coup d’etat in October 2021, which dissolved the civilian-military mixed regime in favour of a pure military junta, and tensions returned once more between the RSF and the Sudanese military top brass.

Like stated at the start of this article, both RSF and the Sudanese military have no problems with Russia or its desire for a Red Sea naval base. The Sudanese military receives most of its equipment from Russia (and China) while the RSF paramilitary transitioned from barely trained irregulars to professional and fully motorized military fighters due to proper training provided by Kremlin-backed Wagner mercenaries.

In fact, the only people that expressed misgivings about the naval base deal were the civilian politicians within the civilian-military mixed regime. They were supposedly worried about national sovereignty. But that issue is now moot because the October 2021 coup d’etat got rid of most of the civilian politicians.

I have seen no evidence that either General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan or RSF leader Hamdan Dagalo is hostile to Russia.

But I see evidence of the military's disdain for the RSF and its refusal to get over the fact that Hamdan Dagalo is a semi-literate civilian parading around in the camouflage uniform of a Lieutenant-General while profiting from a goldmine that ought to be controlled by the Sudanese Federal State.

This is the true cause of the explosion of the gunpowder keg which had been simmering under the flames of a slow burning fire since the creation of RSF by Omar al-Bashir in August 2013.

THE END

Dear reader, if you like my work and feel like making a small donation, then kindly make for my Digital Tip Jar at Buy Me A Coffee

Thank you.

I am glad to connect with you, someone who clearly knows about and does much research on Africa. I was one of those who believed the US started this round of strife what with Blinken’s promise to punish those who failed to support the military/ civilian government US $ 288 m humanitarian aid via the usual NED/ UASID vehicles, Victoria Nuland’s visit and the Red Sea Russian naval base.

However, it seems the issue is another Prigozhin (Or was Progizhin another Dagalo?) dangerous entities under any circumstances. This particular one has now blossomed to manifest the promised danger

And your style is such that the imagery forms very well in the mind….

You have just taken me around the Sudan in 20 minutes… the people, the terrain, the ambience, all of it

Great article, thanks!

I think your 1983 chronology needs to be revised, though: the declaration of Sharia didn't happen until early September 1983, so events in response to that couldn't have occurred in July.